Brick & McClain discuss breaking up with fast food, bad high school poetry, the new $300 Atari, not wanting to be Chief Wiggum, what category this podcast is in, their time travel plans, and Roseanne’s legacy.

|

|

|

|

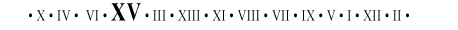

In about a week pre-registration will open for this year’s Final Fantasy V Four Job Fieta. The Fiesta is an annual community event in which players complete Final Fantasy V under some randomly-assigned restrictions. It’s a truly excellent way to enjoy the game and I frequently tell new players that it’s a fine introduction to the game. The Fiesta is such a treat that FFV has supplanted FFIV as my yearly go-to Final Fantasy. That said, Final Fantasy V is not an easy game to complete on your first run through, Fiesta rules or no. As a 5-year Fiesta veteran, I thought I would share some of the wisdom I’ve gleaned with first-time runners, or for people who are on the fence about signing up. – Should I play FFV before trying the Fiesta?Most Fiesta players have completed the game many times, but I think the Fiesta is fine for FFV newbies for one specific reason: Fiesta rules help alleviate Decision Paralysis. There are lots of jobs, abilities, equipment, magic, and combinations of all those things in FFV. The game does very little to explain how any of this works or where the good synergies are. It isn’t like Final Fantasy III, which clearly signposts what jobs to use with gimmick dungeons. It isn’t like Final Fantasy Tactics where you constantly see your jobs in use by enemy opposition, cluing you into strengths and weaknesses. I’ve known several players who stalled out on the game because the prospect of exploring 20 jobs’ worth of mechanics was too daunting a task. In the Fiesta, you are locked into your jobs. Rather than a huge, expansive puzzle of “find the good abilities”, the game is reduced to a series of smaller, more meaningful puzzles involving using and combining abilities from the small pool you’re allowed to use. Playing by Fiesta rules is technically a challenge run, but it’s a very different kind of challenge than playing the vanilla game, which is what I think makes it appropriate for new players. Instead of the nagging feeling that you could be blitzing the game if only you knew the ins-and-outs of your big massive list of jobs, you have a focused series of challenges involving knowledge of only a very few. It’s not, “what on this huge intimidating menu is helpful to me right now, and will it be helpful again later?” But rather, “here are the eight things I can do, what combination of those things will get me through this next boss fight?” – You’re Not AloneFinal Fantasy V is not a game you can figure out based on feedback alone. It is an old 16-bit RPG with a million little things, designed for a pre-Internet world. You do not get big obvious pop-ups when your status spells miss enemies, and there is no big in-game encyclopedia leading you to make good decisions. If you’re going to learn the game, you’re going to have to lean on people. Fortunately, during Fiesta, there are thousands of enthusiastic people playing the game on pretty much every corner of the internet. When you get stuck — and you will get stuck — ask for advice! My own stream chat and Discord server can cheerfully answer any question you might have about the game, and mine is just one of the hundreds of communities that will have some active Fiesta involvement. If you need help but don’t like talking to people, there’s the Four Job Fiesta Support Program, a helpful little app that sits in your system tray and helpfully provides pages and pages of easily-accessible, accurate data specifically tailored to clearing the Fiesta. – How Jobs Are UnlockedIf you’re new to Final Fantasy V, here’s a brief explanation on how new jobs are unlocked. There are three worlds in the game, and the first world involves shattering four crystals. Each time a crystal shatters, several more jobs become available to use. This divides the job pool up by crystal; there are “Wind Jobs” and “Fire Jobs” and so on. This doesn’t mean that the Fire Jobs are jobs that use fire abilties, or whatever, just that they’re the jobs that happen to open up when you shatter the fire crystal. When a crystal shatters (or, if you know the story, a few minutes ahead of time so you can allow for Twitter lag) you tweet at Gilgabot (@FF5ForFutures) to see what your next randomly-assigned job is. From that point on, that job is added to the ones you’re allowed to use. The basic structure of a Fiesta run is something like this:

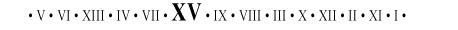

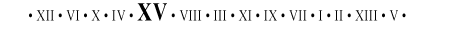

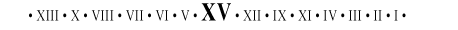

At this point you’re about 30%-ish through the story, so you do get to play the bulk of the game with all your jobs. There is a “secret” job that can be unlocked in the third world, and a few more in the GBA and Steam versions of the game, but those aren’t considered as part of the Fiesta. – Three Ways to RollThere are lots of variants and modifiers on the standard Fiesta rules, based on what hashtags you include in your registration tweet to Gilgabot. I think first-timers should stick to one of these three: #reg is the normal ruleset. Each time you roll for jobs Gilgabot will select one from the crystal you just shattered. This has the potential for a very sticky early game, depending what you roll, but also just about guarantees smooth sailing by the time you’re in the second world. This is because two of the #wind jobs (Thief and White Mage) are notoriously tricky during the single-job slog, while all of the #earth jobs are good enough to carry a team by themselves. It’s not possible to roll multiples of any job. If you can’t wrap your head around all the other fiesta jargon, just go with #reg and don’t sweat the small stuff. #regrand is the random ruleset. Each time you roll for jobs, instead of getting one from the crystal you just shattered, you pull from a list of crystals you just shattered plus all previous crystals. This means the same potential for a sticky early game, as your #wind roll is unchanged. It also biases your party towards #wind and against #earth, since #wind jobs are in the pool for all four rolls, and #earth for only one. Without having crunched a spreadsheet on the topic, I’m betting the difficulty is about even here; you potentially lose the carry of a guaranteed #earth job, but you increase your chances of getting multiple #wind jobs, all of which are pretty good at supporting a team. Because three of your crystals are in the pool more than once, you might end up rolling the same job multiple times. If that happens, just make sure you have that many of that job in your team. If you roll, say, Thief for both #wind and #water, well, first of all, I’m sorry that happened to you. But you then need to have two #regchaos and #regpurechaos put all the jobs into the pool for all four rolls. The difference between the two is #regpurechaos includes Freelancer (the base “job” of not having any job) and Mime (the secret third world job). This does mean you might roll a job you don’t have access to yet; if you get an earth job on your #wind roll, you just have to use Freelancers for a little longer until you get to the proper point in the story. (This is basically okay since Freelancers are actually really good.) The worst case scenario here is if your #wind roll gives you something you can’t use yet, then your #water roll gives you Berserker, which brings us to… – Stay Away from #BERSERKERRISKMost jobs in Final Fantasy V are good, or at least “good enough”, but there is one in particular that is a real dud: the Berserker. The Fiesta event organizers know this, and created the #BERSERKERRISK tag. The way this works is, for every $x they raise for charity (oh, the Fiesta is a charity event, I guess I hadn’t mentioned that before) one Berserker is added to the #BERSERKERRISK pool. If you add #BERSERKERRISK to your registration tweet, one of your rolls is replaced with a Berserker from the pool. The more cash they take in, the more Berserkers they spit out, and there are a couple unlucky souls who end up running the dreaded QUADZERKER.

Berserkers can’t be controlled, can’t use abilities, are super slow, miss a lot, and waste lots of turns targeting the wrong enemies. They’re also a water crystal job, which means they appear pretty early, and there are several places in the first world where they are pure liability. In general, having a Berserker on your team isn’t that bad. It’s just that Fiesta rules introduce a few edge cases where you end up using only Berserkers as your main source of damage, and that’s problematic. These edge cases don’t really make the run more challenging in any meaningful sense; the solution is always to either grind out levels or retry the fight until you get lucky. Most people who quit the Fiesta do so because of situations like this, so if it’s your first go-round, you might want to consider avoiding it. There are still a few cases where you might find yourself saddled with a Berserker at lousy times. The worst possible #reg start is Thief/Berserker, which almost caused me to quit during my first year, and I’m an absolute Final Fantasy maniac. #regrand puts Berserker in your pool for three out of the four rolls, which means you may end up with multiples. #regchaos and #regpurechaos puts Berserker in your pool for all your rolls. If you end up in one of these unlucky situations, though, you do have a remedy. – Buy Your Way to VictoryIf you find yourself with an untenable party, and the expert feedback is something like “you can steal Hi-Potions from a rare monster in a forest halfway across the map”, you still have a way out: the Job Fair. Job Fair is where you go to “buy away” bad jobs with cash money, in the form of charity donations. It’s $3 to re-roll a crystal, if all you want to do is get rid of your #water Berserker, or a set price to replace that Berserker with another job. Prices vary from $1 for “bad” jobs to $5 for the unquestionably best ones. As for what to buy from the Job Fair, that’s going to depend largely on what the rest of your jobs are. In general, you’ll be replacing a job you don’t like with something you need. This is the kind of thing the great and knowledgable Internet hivemind can help you with. That being said, I feel like I can offer these useful tips:

– The Single-Job SlogNow that we’ve covered the basics, let’s talk about some of the more specific troubles you might have. The first of these is in the very early game, in between your #wind and #water rolls, where you’re forced to use four heroes with the same job. You have to get through four boss fights with your single-job team, including a dungeon that blocks you off from visiting town to re-stock. Kind of a mean trick, so here are some tips: Thief has the hardest road. There are no good Thief weapons in the first town, so stock up on A LOT of Potions. There’s a free healing pot in the Wind Shrine; consider camping out there and gaining enough ABPs to learn !Flee. Once you’re in the Ship Graveyard (with A LOT of Potions!), the Skeletons there will drop Daggers for you to use. You can damage them with Potions, and !Flee from everything else. You can !Steal more Potions from the water weird guys and the rock golemn guys. Your next upgrade is in Walse Tower, where you can !Steal Mythril Knives from Wyverns. Hope your #water job isn’t Berserker! White Mage is a slow start, but thanks to early Cure magic, not a particularly difficult one. You’ll find a Flail in a treasure box early in the Ship Graveyard, which is the best damage output you’ll have until #water. Your worst #water job is probably Time Mage, because that will mean going through the middle of world one with very little damage output, but take heart in the fact that both of these jobs are absolutely excellent in the late game. Monk is a straightforward job; just punch things until they die. (Alternately: !Kick things until they die.) Keep in mind your only source of early healing is Potions, and you have no way to get more of them in the Ship Graveyard. Knight is probably the easiest of the single-job slogs. You won’t have any major difficulties. The only top that makes sense is to make sure all four of your Knights are equipped before entering the canal, since that’s when you’ll lose access to shops for a while. (You can treat Freelancer like Knight in the early game, in case you rolled #regchaos and got a job you can’t use yet.) Black Mage is one of the undisputed strongest jobs in the game, start to finish. As long as you buy the Fire, Blizzard and Thunder spells in the first town, you should breeze all the way to your #water job. Blue Mage is like a slightly weaker Knight, and can clear the early game just on the strength of their equipment set. That being said, it’s a bit of a weird claptrap job, and will take some work to develop properly. In particular, make sure to get the Aero spell from Moldwynds in the Wind Shrine, and Vampire from the bats in the Pirate Cave. These two spells are excellent and can largely carry the job through the whole game if you can’t be arsed to go spell-hunting ever again. – Some Sticking PointsAs awesome as the Fiesta is, FFV was obviously not designed with the challenge in mind. There are a few notorious points in the game where certain party configurations can stall out. Here’s some general tips for the most common ones: Byblos makes use of Protect, Dischord, and countering attacks with Drain to make him a big roadblock for low-damage parties. The longer you can stay in this fight, the greater your chances of running him out of MP so he can no longer Drain for more damage than you can deal. Thieves can !Steal Hi-Potions on the steam ship, White Mages can make use of the Heal Staff to stall. Knights, Monks and the like may find themselves on the losing end here if they get their levels chopped too much with Dischord. There’s no clever “Aha!” solution to this fight, it’s just long and you may have to retry it a couple times. Sand Worm isn’t a terribly tricky fight, but it’s the first major one where Berserkers are a huge liability. Attacking empty holes in this fight causes a Gravity counterattack, which will sap your HP much faster than you can heal it back. The way to deal with this is to go into the fight with your Berserker already dead. Purobolos are a big group of gimmick-y bombs. Their HP is low, but if you kill one it will cast a revive spell that brings all the dead ones back to life. If they Self-Destruct they won’t revive anyone, but it will also deal a huge amount of damage. Unless you can kill them all at the same time, you’re going to have to get clever. One way to do it is to wait for one to explode, then immediately revive the hero they killed, and do that until the last one is gone. Titan will use Earth Shaker when you kill him. If your party doesn’t have enough HP to survive this, chances are they have some way of inflicting Confuse. Go back to North Mountain, confuse a Gaelicat, and it will put Float on your heroes for you. Atomos is a gimmick fight. He’ll spam Comet at you until someone dies, then slowly drag the dead hero across the map. Pile on damage while this hs happening, then revive the dead hero just before they get engulfed. This maximizes the time you can spend attacking while minimizing the time spent eating Comets. There are some hilariously easy ways to win this fight, but a few teams have access to none of them. Crystal Guardians are the four nameless crystal monsters you fight at the end of the big tree. Each of these is attuned to a particular element, and will spam powerful spells of that element at below half health. The trick here is to deal about ~4500 damage to one, then slam it with all your most powerful attacks at once to take it out before things get out of hand. (How best to do that is going to vary from party to party.) One trick to keep in mind is none of the crystals are immune to instand death attacks, if you have access to them. Exdeath is the final boss of the second world. In some ways this is the hardest boss in the game. Except for one strategy involving a Bard, some ridiculous setup, and hours of waiting, there’s no way to win this fight without just piling on the damage and keeping ahead of the healing. Parties which can’t put out damage and can’t heal themselves have a lot of trouble here. This is a case where tapping the hivemind can pay off in spades, although be advised there are some specific setups where the only good advice is “level up and then get lucky”. One thing that’s easy to control is avoiding his L3 Flare spell; simply make sure no hero has a level divisible by three, and these rounds turn into freebies. World three is where the game opens up quite a bit, and you gain access to a great deal of secondary advantages in the form of new equipment. If you’ve made it to world three, you’re a savvy enough player to go all the way. A lot of the troublesome bosses in this stage of the game are optional, so step one is to make sure you know a boss is gating off something you want to get for the jobs you have. If not, the only reason to fight them is for street cred. The good news is that, with some clever planning, most any party now has access to most forms of status effects, and some universally-good damage options become available. Know what’s available and where to go, and you should be able to navigate to the endgame with only a little fuss. – The Triple CrownThe triple crown refers to the three endgame bosses of Final Fantasy V: Neo Exdeath (who needs to be destroyed in order to complete the game and claim victory), Omega and Shinryu. You don’t have to beat Omega and Shinryu in order to claim you finished the Fiesta, but Gilgabot might think less of you unless you do. In truth, these bosses are difficult but not implausibly so. It’s very rare for a fiesta party to have literally no answer to these fights, and in some cases they can be won with clever application of just one single ability. For example, any party capable of inflicting Berserk can win against Shinryu, and ten out of the twenty-ish jobs can do this. As a matter of fact, during one year’s Fiesta, Neo Exdeath was my big problem — not either of the “super” bosses! I guess my advice here is, give the Triple Crown an honest try. It’s fun to just throw a party against these heavyweights and just laughing at how quickly you get destroyed, but there are ways to fell them and you could explore that. Think of how fun it would be if you got the Triple Crown on your very first Fiesta. With three Berserkers. Okay, maybe not that last thing. If you’re a new DM running your first campaign and looking for advice, one of the worst things you could do would be to read the various D&D blogs and subreddits and take what they say as gospel. Don’t get me wrong, there are a lot of excellent and experienced DMs out there, each with their own well of wisdom from which you might drink. But there are also a lot of memes and ideas floating around the current D&D culture which, if applied without care, would preclude a lot of the types of fun you could be having with the game. Put another way: Critical Role is an excellent example of D&D, but it’s not the only thing D&D is. In this post I’ll explore four of the most pervasive pieces of New DM Advice I see bandied about and explain why it might be appropriate to ignore them. To be very clear: all of these points are things you should be familiar with, as a DM. They are powerful storytelling and adjucation tools. But they are not a Bible. They should be in your toolbox, to be applied properly and with care, not axioms to slavishly adhere to. In general, any DM advice that includes words like “always” and “never” should be taken with a grain of salt. Keep in mind that every DM who gives you advice, including me, is speaking from a biased position. Nobody knows your table except for you, and even you don’t know your table if you’re still new. DMing is a skill, and like all skills, you’re going to be bad at it until you’re good. But playing is a skill too, and your players are going to take their cues from you. They might not be reading the same subreddits you are. Applying advice you got on the internet without really examining it may send dangerous messages to new players and result in Bad Funtimes. The goal of this bloggy-post is to minimize that damage at your table. With that in mind, let’s crack some popular DM memes! – “Yes, and…”The idea here is, when your players have an idea, you should not shut them down. Instead of saying “No,” you find a way to build the scene by saying, “Yes, and this is what happens next.” (Or, “Yes, but this happens too.”) The practice stems from the improv scene, where trained actors build spontaneous stories by taking each others’ suggestions and adding to them. In some sense, D&D is a form of improv, and the concept does translate in a lot of circumstances. But D&D is a game of rules, and your players are not trained actors. If you commit to “yes, and…” you can expect your game to immediately go in directions you did not intend, and aren’t equipped to handle. What your players might hear: “I will never say no.” Like spoiled little chocolate-smeared children, your players are going to have to hear “no” a lot. It’s the only way they’ll learn. For one, because D&D is a game with rules, “yes, and…” is not an appropriate response to any action that breaks a rule. If you allow this kind of thing at your table players are going to pick up on the idea that breaking rules is fine, and they’ll do it more and more, until you may as well just burn all your books. And for another, new players tend to not act in good faith. They want to do things they think are cool or funny without any regard to how it will affect your world. Worst of all, if you’ve trained your players that “no” isn’t in your vocabulary, and your game gets into a terrible state as a result, you now cannot fix the problem by starting to say “no”. Players who have gotten away with murder (literally, in some cases!) will feel like you’ve broken a promise if you suddenly take away their “yes, and…” superpowers. Here are some actions new players are notorious for trying, in case you’re still considering a primarily “yes, and…” approach to the game:

If those all sound conducive to a reasonable heroic fantasy adventure story that you’d like to tell, by all means, let your players run amok. Here’s what I’m not saying: “Find reasons to say no.” Your first instinct, when players declare an action that sounds a little strange or unorthodox, should not be to shut it down. This is especially true if it’s tied to a spell or class feature. Players take these things because they sound cool and they want to use them; nothing degrades their faith and good cheer faster than not being told they can’t! The spirit of “yes, and…” is to take reasonable-sounding suggestions and build memorable scenes out of them. With some experience, you’ll learn which suggestions are good for your world and which aren’t. If you’re going out of your way to say no as often as possible you are being unnecessarily adversarial. In this case you’re training your players to not try interesting things, because they know beforehand you’ll shut them down, and months of tepid statblock reading shall be your reward. Here’s what I suggest: “Say yes as often as possible, unless you need to say no, then for the love of god SAY NO.” Instead of training your playes that any lulzy thing that pops into their head is fair game, or that actions not strictly codified on their character sheets are verboten, train them to know the limits of your setting and of the rules, and to act within them. Commit to building scenes that work, rather than just any old scene your players come up with. – Fail ForwardOr, “Success at a Cost”. The idea here is that players should advance even when they fail. This is usually applied to skill checks, but not universally so; I also see the concept applied to saving throws and, in extreme cases, party wipes. New players hate failing, so twisting their failures into interesting story beats is a good way to soften the blow. Of all the points on this list, I am least convinced Fail Forward is a universal storytelling tool. It’s surely the least-used tool in my box, maybe like an awl. I see Fail Forward preached as a way to keep the story moving when the players get stuck, or to alleviate the sting of an uninteresting roll outcome, or to make sure adventures don’t get bottlenecked by a single un-repeatable check. I try to avoid these things too, I just have other methods for handling them. I’ve read countless examples of Fail Forward stories on this here internet of ours, and while some have made for memorable stories others just seem contrived and arbitrary. One example that pops up time and time again is a rogue picking the lock on a door. The rest of the adventure is behind the door, so if the rogue fails on the lockpick check, the party can’t continue. Some examples of how to Fail Forward in this situation include:

In my estimation, these are all terrible resolutions to the problem of this stupid door, and the real solution is something like “there are other ways to get through the door.” Telling the rogue her failed roll pops the door anyway except now there are guards there is robbing the barbarian of the chance to bash it down, the wizard of the chance to cast knock, or the bard of the chance to sweet-talk a housemaid out of a key. What your players might hear: “Success is guaranteed.” If you don’t let your players fail, they won’t learn to deal with failure. They won’t learn to come up with creative solutions to problems. Instead, they will learn that every door opens, no matter what, just sometimes there are guards waiting on the other side. There’s no incentive to think laterally or prepare backup plans, because the first thing they try will work and the penalty that’s applied for “failure” is just a fact of life. (And probably not even that big a deal. What self-respecting rogue runs around with only one lockpick?) Here’s what I’m not saying: “Failure should result in punishment.” The flip side of this coin is being unnecessarily punitive on a failed check. A creative DM can no doubt think of ways to punish every bad skill check in the book, from rocks falling to alarm klaxons blaring to god-only-knows-what. This is of course just as absurd as guards materializing on the other side of a locked door. In practice, most skill checks don’t result in an actual fail state; they simply maintain the status quo. The rogue failed with her lockpicks; the door remains closed. The cleric failed his Athletics check; he’s still at the bottom of the cliff. The ranger failed on Perception; he doesn’t know there are orcs nearby (and didn’t a moment ago, either). These situations don’t need an extra layer of punishment and there’s nothing sporting about concocting one. Here’s what I suggest: “Know what failure means beforehand.” When planning encounters with skill checks, know ahead of time what failure is going to mean. Cases where failure and success both lead to interesting results are usually pretty apparent. A quick line in your notes explaining what happens on a pass and what happens on a fail is probably all you need: “The guard captain can be convinced to release the prisoner with an Intimidation check, but on a failure he demands a 20 gp bribe.” For the rest of the cases where failure simply leads to the status quo, leave it alone and let the players think around the problem. This does require planning, and it takes practice to get right. Every DM has a horror story about players failing to answer some magic mouth riddle, and then all failing their Intelligence checks, and having to spawn in a helper NPC who just so happens to know the solution. These are bad scenes and the only real way to deal with them is to use Plot Spackle for now and do a better job next time. – Player AgencyThere is a very long list of things the DM can do to “remove player agency”. As best I can figure, player agency means something like “the player’s ability to make choices for his or her character.” This is utter nonsense and you would do well to discard such silly notions. Players do not make choices, for their characters or otherwise, and they are not in control. If you’ve played in or watched one of my D&D campaigns, it may surprise you that I take such a hardline stance. But it is necessary to maintain my sanity. You might say you’ve seen lots of instances where my players made choices, or declared actions, and then things happened in the game. Like maybe one of my players said, “I attack that orc,” and then they attacked that orc. What you witnessed, though, was a tacit agreement between my players and I to simply cut out the redundant middle-man. What actually happened was my player asked me, very politely, for permission to attack that orc. And then I — not they — made the choice to allow that to happen in my game world. “Yes, you may attack that orc” may be the most common response to the implied question of an attack roll, but it is by no means the only one. Other perfectly valid choices on my behalf would be, “No, you may not attack that orc.” Or, “No, the orc attacks you instead.” Or, “Zap! You’re all cows now! Moooooo!” No player has ever overruled a DM at his own table, without that DM’s cooperation. Simply by virtue of being the DM, anything he says happens and anything he doesn’t say doesn’t happen. I’m sorry if you’ve been led to believe otherwise, but no, players simply do not have any sort of agency in that kind of environment. What your players might hear: “You’re more important than I am.” If you insist on allowing your players to have real agency, rather than the carefully-crafted illusion of same, prepare for many arguments. It is trivially easy to find examples of players running roughshod over their DM in practically every D&D community that shares horror stories. In the most extreme cases you will find players (who have never DM’d a game, in all likelihood) who preach the DM’s job is to provide a fun world for the players, full stop. In actuality, the DM is a player himself, and is also trying to have fun. If he’s not having fun, the game will cease to exist in every meaningful way. The DM is the most important guy at the table, bar none. It’s not even a contest. The number one killer of campaigns, in my own 20+ years of experience, is DM burnout. The biggest contributor to DM burnout is a loss of interest because of entitled players making demands, provoking ceaseless arguments, or blatantly sabotaging the game. And players can only get to that point if the DM cedes control to them. Here’s what I’m not saying: “Be a merciless god-tyrant!” Of course, in practice, I am not a tyrant and I do not treat my players like slaves. Because there is one important choice players get to make, and they are making it constantly: “Should I keep playing in this campaign?” A DM who runs his game like an unyeilding control freak is a DM who eventually finds himself without any players. It’s one thing to be in control. It’s another thing to abuse that control to the point where players no longer want to play. For every “my players went berserk and I burned out” story, there are ten “my DM was a sack of butts so I quit playing” stories. Here’s what I suggest: “Players are at your mercy, but they’re still your friends.” If a group of players do you the honor of putting you in a position of power over them, you should banish from your mind any thought of betraying that trust. Ostensibly these people are your friends, your co-workers, your IRC buddies, or your fellow game store enthusiasts. Treat them as such. Own up to mistakes. Listen to criticism. Laugh at yourself. Be humble. Most importantly, don’t make rulings that would cause you, as a player, to quit a game. Find a way to be a benevolent dictator, and your players will love you for it. – “Did everyone have fun?”Perhaps the most common response I see to new DMs soliciting feedback from the internet hivemind is some form of, “Did you ask everyone if they had fun? They said yes? Then there’s no problem!” But there is a problem. Even though everyone had a good time, that DM still felt some niggling doubt that caused him to go seeking advice. That means there’s something wrong, and it can be very difficult to pinpoint what that something might be. D&D is fun, but as we all know, fun comes in lots of shapes and sizes. It’s entirely possible for a new DM to have a vision in his head about what running the game will be like, but then the actual session didn’t meet those expectations, for whatever reason. Yeah, everyone enjoyed themselves, but he was expecting 100 Fun Units™ and ended up only getting 70 Fun Units™. Maybe our poor new DM just had unrealistic ideas about his game fueled by too many professional podcasts. But maybe, just maybe, his vision is attainable if he could only figure out the trick to make it all work. What your players might hear: “This is the most fun we can be having.” You played D&D and it was fun. That’s great! But you could be having more fun, or a different kind of fun. Setting the goodtimes bar too low is a great way to make players lose interest in a campaign. New players will have a fine time with pretty much any style of D&D, from carefully constructed professional modules all the way down to wanton slaughter of the peasantry. It’s new to them, and novelty breeds excitement. But that excitement will fade, and what you’re left with is what you’re left with. Here’s what I’m not saying: “There are wrong ways to have fun!” If wanton slaughter of the peasantry is what your table wants, and you’re happy to provide, then that’s the game you ought to run. I don’t kinkshame. You do you. Lots of DMs will read this post and insist that my table isn’t fun. After all, I earned my kicks back in Second Edition, when men were Men, lawful good meant Lawful Good, magic-users feared housecats, and THAC0 charts spread across the landscape as far as the eye could see. I let my players fail, I let them get stuck, and I do nothing to hide my delight as I murder them with encounters designed for parties twice their strength. I make them track ammo and roleplay through mind control and force them into impossibly depraved moral quandaries. Not everyone wants to play at my table. Maybe you don’t. And maybe I don’t want to play at yours. This is all fine, and perfectly natural. What we should both be doing though, with every session, is searching for new ways to have fun. We should be challenging ourselves to squeeze more and more out of the game. Here’s what I suggest: “Solicit feedback. Act on it. And practice, practice, practice!” Sometimes I ask my players if they had fun, and they tell me, “No, and here’s why.” Repeated iterations of this process is what has helped me to skill up as a DM. The reason this tepid mantra has calcified in the community is because it’s easy. “You had fun, job done, hands washed!” is a decent way to encourage a new DM to keep doing what they’re doing, despite their misgivings, without actually addressing the misgivings. The real answer is a lot harder: figure out what your players want, figure out what you want, find the space where those things overlap, and then keep doing new things in that space for as long as you can hold it together. This is really tough to do. You’re not going to find that spot without putting in the work. You’re going to have to actually talk to your players, and they’re going to have to be honest with you. They’re going to tell you that you suck, and you’re going to have to go back to the drawing board to fix the things that didn’t work and highlight the things that did. It’s a never-ending process, and at times, it can be exhausting. But it’s worth it. If you commit to growing as a DM, to keep trying new things and pushing for new experiences, you will be having More Fun™ than groups who just stack up the orcs week after week. And every so often you’ll touch a raw nerve that really shocks and excites everyone, and those are the stories players and DMs alike will remember forever. Those are the stories that draw new players to the game. – D&D is not a video game. There are no cheat codes, no killer strats, and no instruction manual. Advice can be great, but all any DM can really offer you is an explanation for what works at their table, with the hope that the same will work at yours. Best of luck to you and your table. Thanks for reading!  Doesn’t matter, I’m here anyway. So wait, [impossible thing]!? For most of these answers I’m going to assume the question is being asked in good faith, and respond appropriately. Before that, though, I need to swat away many thousands of mildly obnoxious questions by assuming they aren’t asked in good faith. It’s important to understand that “Unanswered Questions in X!” style clickbait lists are usually not written from the standpoint of a sincere fan seeking clarification, but from that of an internet humorist making fun of confusing stories. The story of the Metal Gear saga is so confusing that it’s become something of a poster child. These questions often take the form of an eye-rolling “so wait.” So wait, are you telling me that Bumblebee Man can really spit hornets? And Quiet has to always be naked? And trained combat veterans think it’s nighttime because they heard an owl? And a gun can have infinite ammo? And angry ghosts and 6-year-old computer programmers and voodoo dolls and diaper monkey? Yes, that’s what I’m telling you. The answer to the question of why these things happen is because those are the things that happened. When folks ask “what’s the deal with diaper monkey” what they mean is “diaper monkey is stupid.” They’re posing their opinion as a rhetorical question. It’s okay to think things are stupid, especially in Metal Gear, which contains 65% of your daily allotment of stupid by volume. But let’s call it what it is. I’m fine with folks thinking Quiet’s nakedness is dumb; I take issue with folks pretending as though the game doesn’t offer an explantion, dumb as that explanation might be. – But no really, why does Quiet have to be naked? She breathes through her skin, and wearing clothes or being submerged in water causes her to suffocate.  And there’s a mod to make her even naked-er, because of course there is. Yeah, but see, that’s stupid! Sure, but that doesn’t make it not the answer to the question. It also brings us to this uncomfortable truth: the answers aren’t going to please everyone. There comes a point where a given person will find no possible answer satisfying, because of some fundamental disconnect with the source material as presented. I find the biggest disconnect when it comes to Metal Gear is this: in the Metal Gear universe, magic is real. To a lot of burning questions, the answer is simply, “Magic, full stop.” And by magic I mean literal, supernatural, Harry-Potter-and-Gandalf magic. Mushrooms recharge batteries because magic. Infinite ammo bandana, because magic. Guy takes headshot and runs on water because magic. Mean psychic ghost because magic. Immortal horse because magic. Kuwabara kuwabara, because magic. Sometimes the magic hides behind SCIENCE!. Vampire man because SCIENCE!, perfect stealth camo because SCIENCE!, flying rocket arm because SCIENCE!. But when you dig deep into these and try to explain the science, eventually you hit magic. The Phantom Pain falls all over itself desperately trying to explain the biology behind vocal chord parasites, but the idea is just incompatible with our understanding of the physical sciences, and it’s magic the rest of the way down. Whether you start at Metal Gear, the first published game, or Snake Eater, the first chapter chronologically, the series establishes supernatural elements early on and never lets up. If “a wizard did it” doesn’t sate your curiosity as to why there are insta-death hamsters and talking ghost arms in your sci-fi tactical espionage story, it’s likely because some part of you just doesn’t want them there. – Are nanomachines magic? No, but kinda. Nanomachines (or, in The Phantom Pain parlance, parasites) are not, in the “magic is real” sense outlined above, magic. They aren’t supernatural, and there is at least one person — Naomi Hunter — who knows exactly how they work and what they can do. Shortest explanation ever: they are cell-sized machines injected into the bloodstream which re-program the human body. In the narrative sense, they are a kind of “plot magic”. They’re a catch-all explanation for any weird or nonsensical thing characters need to be able to do in Metal Gear, which Kojima did not want to attribute to supernatural forces. – Have we established enough of a baseline now to start asking real questions? Yes. Yes we have. Let’s start with an easy one. – Which games are canon? The Metal Gear timeline consists of nine games:

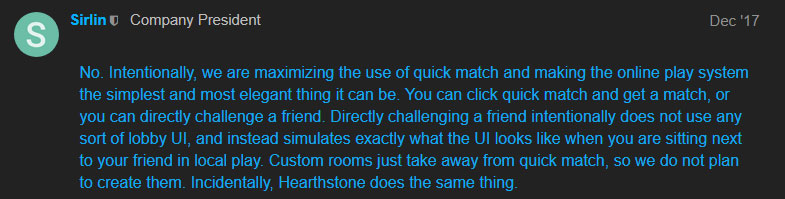

This series is mostly about guns and mustaches. Are Portable Ops and Rising canon? They are if you want them to be. Truth is, it doesn’t matter. Nothing happens in these two titles that directly contradicts the other games; the timeline works whether you include or omit them. – Why does Naked Snake have a Raiden mask in his inventory? He doesn’t. He has an Ivan Raidenovich Raikov mask. In a radio conversation about the mask, SIGINT explains he developed the eerily lifelike Raikov mask for an operation to infiltrate GRU. The operation was scrapped before the mask was used, but SIGINT was so impressed with his own work that he squirreled it onto Snake’s person before Operation: Snake Eater, you know, just in case he needed it. There is no in-universe reason for Raikov and Raiden’s similarities. Sometimes people — even weird albino prettyboy people — look like one another. – Where was Grey Fox during The Phantom Pain? (etc.) This is the most common form of “unanswered” Metal Gear question. In a franchise featuring dozens of characters and spanning six console generations, some folks are unsatisfied without a complete accurate timeline of every character’s life. Grey Fox is the fan favorite, but there are others: Ocelot during Peace Walker? Raiden during Metal Gear Solid? Colonel Campbell during Sons of Liberty? Dr. Madnar during, well, any of it? The answer is: it doesn’t matter. Wherever those characters were, and whatever they were doing, they weren’t integral to the story in question, and their actions didn’t shape the structure of the narrative as a whole. They weren’t in those games because they weren’t in them. Still, it’s pretty easy to infer what a character was doing during the gaps in their timeline. We know Grey Fox kills Naomi Hunter’s parents at some point in the late 70s or early 80s while Big Boss is in a coma. Over a decade later he becomes a decorated member of FOXHOUND, gets punched to death by Snake in Zanzibar Land, then is revived as the Cyborg Ninja. In the intervening time, during the late 80s and early 90s, he was probably working with Big Boss. Remember, we don’t actually play as Big Boss in The Phantom Pain; we play as Venom Snake. It makes perfect sense for a character to be working for Big Boss during that timeframe, because Big Boss is off somewhere else, doing Big Boss things. While Venom is playing grab-ass with Skull Face in Afghanistan, Big Boss is elsewhere, making contact with Sniper Wolf, Vulcan Raven, Decoy Octopus and, yes, Grey Fox. – What does Code Talker mean by “Eyes on Kazuhira”? This is a particularly frustrating loose end, because it stinks of a plot thread abandoned because The Phantom Pain was woefully unfinished. Lacking some definitive answer, we can infer what Code Talker probably meant in the context of the rest of his other nonsensical parasite-stasis word salad. Kaz Miller is, putting it delicately, not the most well-adjusted man on the oil rig. He has been viciously tortured, mind and body. He has been cruelly and — from his perspective, unnecessarily — manipulated by Cipher. Everything he ever built has been destroyed, and then he finds out the man he reveres most, Big Boss, abandoned him and pawned him off on a secret doppelganger. This fact was revealed in trust to Ocelot rather than himself. Kaz doesn’t work with Venom or Big Boss at any point after The Phantom Pain, and the break-up is not amicable. He chooses to support Solid Snake instead, and as of Metal Gear 2 is actively working against Big Boss’s interests. He is a bitter man, obsessed with revenge, who spends the entirety of The Phantom Pain railing against the other Diamond Dogs high-ups. Oh, and he extorts money to secretly invest in a hamburger restaurant. So hey, “Big Boss”, keep your eyes on that Kazuhira Miller. He’s a loose cannon set to go off. – When did Big Boss become a villain? This is one of the hottest Metal Gear questions out there, and one of the easiest to tackle, because the answer is “…seriously?” As in, “Weren’t you paying attention?” The marketing blitz for The Phantom Pain led a lot of players to believe we would get a definitive, clear-cut moment where Big Boss stopped being a “good guy” and started being a “bad guy”. This ended up not happening, which should be not at all surprising to anyone who played the previous few games. Depending on your perspective, Big Boss was never a “good guy” in the first place.  Pictured: a good guy. (Maybe.) During his denouement in Guns of the Patriots, Big Boss says, “Ever since the day I killed The Boss… with my own hands… I was already dead.” If you need a singular moment in time where Big Boss lost his path, that was probably it. Or, you could answer this by simply saying “Peace Walker“. That game has Big Boss doing all the things that made him the villain of the MSX games: building a private army, stealing resources, deploying child soldiers, seizing nuclear weapons, developing Metal Gear. Of course, we-the-player didn’t recognize Big Boss as a “bad guy” in that game because the story is told from his perspective. When he’s up to all those same shenanigans in Zanzibar Land, and our controller is plugged into Solid Snake instead, things look very different to us. The broadest explanation is that Metal Gear is not a story about “good guys” and “bad guys”. It is not Star Wars. With the possible exceptions of Colonel Volgin and Psycho Mantis, most every character in the saga has sympathetic motives. Even Ocelot, in his own crazy way. – How did Big Boss go back to the US? And why? He didn’t. Venom Snake did, posing as Big Boss. – Okay, smart ass, how did Venom Snake go back to the US? And why? We don’t have a lot of data on the particulars. When the games do reference this, it’s always in passing. The timeline roll from The Phantom Pain simply says “1995: While commanding special forces unit FOXHOUND from a position in the US military…” and glosses over the transition. I’m betting the answer is surprisingly boring, though. The US didn’t want Big Boss to leave in the first place, so when “he” offered to come back, they welcomed “him” openly. Big Boss (or Venom Snake, who from the perspective of the US military effectively is Big Boss) spent the decade after Snake Eater trying to build his private army, somewhat unsuccessfully. He finally gets established in Peace Walker, but doesn’t actively work against the US’s interests. He stops the maniacal plan of a rogue CIA chief, saving America from a huge headache. During that mission he speaks directly to agents at NORAD, and those Americans who know him personally have great veneration for him. Absent any evidence of MSF or Diamond Dogs openly declaring war against the US or one of its allies, it’s reasonable to conclude that Venom-as-Big-Boss just rolled up at some point in the early ’90s and said, “Hey guys, I got all that private army stuff out of my system, I’m ready to come home and work for Uncle Sam again.” As for why, well, one of the most useful places you can be if you’re setting up a rogue military country like Outer Heaven or Zanzibar Land would be amidst America’s top brass. Indeed, the big twist of the original Metal Gear is that “Big Boss” tried to sabotage the mission by sending an unproven soldier on what was supposed to be a suicide mission. Unfortunately that soldier was Solid Snake and things did not end well for either Big Boss. – Where was Solid Snake raised? The Les Enfants Terribles program was masterminded by Zero and The Patriots, but was officially developed by the US government. Eli (Liquid Snake) was sent to the UK and eventually escaped. We’re never explicitly told what happened to David (Solid Snake), except that by 1991 he was “sent to the battlefield”. We do know that Snake was a Green Beret and later a member of FOXHOUND, both of which are American military organizations. All signs point to Liquid’s infodump at the end of Metal Gear Solid being accurate: the US military kept a watchful eye on Solid Snake, grooming him to eventually become the next Big Boss. – What ever happened with OILIX? Nothing. For some reason, Dr. Marv’s research was never implemented, and his work was never duplicated after he died. There are numerous possible explanations. Maybe the data cartridge recovered at the end of Metal Gear 2 was corrupted by chocolate or hamster droppings. Maybe it was stolen by Russian double agents or supressed by The Patriots. Maybe OILIX was Marv’s scientific superpower and it was just impossible to implement without him. Maybe there was a critical flaw in the production process that wasn’t spotted until after Marv’s death. Maybe it was eaten by Y2k. At some point in the five years between Metal Gear 2 and Metal Gear Solid the oil crisis was resolved to such satisfaction that OILIX became unnecessary. – Is Dr. Clark male or female? Female. Dr. Clark is Para-medic. There is a lot of in-universe misinformation surrounding Dr. Clark. There are conflicting reports as to her identity in the ’90s because she is a Patriots founding member doing cutting edge (and highly illegal) research involving cloning, cybernetics, and just a smidge of human torture. People who know of her work but have never met her personally, such as Naomi Hunter, assume Dr. Clark is a man because most mad scientists turn out to be men. The people who have met her personally were probably all murdered by the Cyborg Ninja. – Which Metal Gear Solid ending is canon? Whichever one you want. The two endings exist in a kind of continuity superposition, and the rest of the timeline works whether Snake escapes with Meryl or Otacon. Whichever one he doesn’t rescue somehow miraculously survives. If there’s one thing Metal Gear is good at, it’s having important (and sometimes not-so-important) characters miraculously survive offscreen. (And sometimes onscreen!) Either way, Snake and Meryl persue a brief romantic interlude, then go their separate ways. Meryl ends up working for the Army in Rat Patrol 01, Snake ends up founding Philanthropy with Otacon, and he has both the stealth camo and infinite ammo bandana as of Sons of Liberty. Lucky bastard.  “…where we immediately break up and go back to what we were already doing.” What does La-li-lu-le-lo mean? The La-li-lu-le-lo are The Patriots. Specifically, it’s the string of syllables second-level agents of The Patriots are programmed by nanomachines to hear and say instead of “The Patriots”. It works a bit like content filters on web forums. When an agent’s nanomachines detects the phrase “The Patriots” in reference to the secret shadowy organization nobody is supposed to know about, they covertly replace the words with “La-li-lu-le-lo” in the agent’s brain. Such second-level agents include Scott Dolph, Richard Ames, and Meryl Silverburgh; basically anyone The Patriots want to make use of without revealing themselves to. It is never revealed how the nanomachines can differentiate usage of their name from, say, the sportsball team. – Why is Solidus so much older than Liquid and Solid Snake? Solidus is actually younger, by a couple of years. All of Big Boss’s clones were genetically modified to age faster than normal humans. This is why Snake looks like a 70-year-old math teacher in Guns of the Patriots. Solidus must have been modified to age at an even more accelerated rate. Why would The Patriots do this? Les Enfants Terribles was the final straw for Big Boss, and the moment he decided to break away from Zero. Once this happened, Zero must have been more desperate than ever for a Big Boss figurehead to his organization. When the perfect clone — Solidus — was implanted, he put a rush job on things. 25 years later Solidus looks like a 50-year-old man, and is put into place as POTUS. – Why does Raiden keep leaving Rose? Sons of Liberty and Guns of the Patriots both end with Raiden reconnecting with his lady lover Rosemary, only to be back to his old emo-ninja’ing self in time for the next title. Leaving aside the joke answer of Rose being a horrible shrew nobody would want to stay married to, it turns out it’s pretty hard for a genetically-altered and deeply-traumatized homicidal supersoldier jacked up on nanomachines to stay settled. After a short time playing house Raiden feels drawn back to the battlefield, just like the countless legendary soldiers before him. – What happened to Naomi and Mei-Ling’s accents? Canonically, these two characters have American accents. Around the time of Sons of Liberty, a remake of the original Metal Gear Solid came out for Nintendo Gamecube called The Twin Snakes. The game had updated graphics, re-dubbed audio, and improved gameplay, but is considered non-canonical by later sequels. Whenever flashback footage of Metal Gear Solid is shown in later games, it is consistently pulled from the PS1 original, as though the whole Metal Gear universe were made of low-poly models in the mid-aughts. The one exception is the voice acting. Metal Gear Solid has legendarily poor quality voice acting, so when it came time to put various audio clips into Guns of the Patriots cutscenes, they were pulled from The Twin Snakes instead. As for why the accents were changed for The Twin Snakes, that’s anyone’s guess. – How have The Patriots been dead for over 100 years? They aren’t dead, at least, not all of them. As of the end of Sons of Liberty, when this twist is revealed, Patriots founders Ocelot and EVA are still alive and working. Big Boss and Zero are biologically alive, but no longer active because of various Patriots machinations. And none of them are 100 years old. It is revealed in Guns of the Patriots that the identities Snake and Raiden pulled out of GW were bogus, because part of how Cipher hides The Patriots is with layers and layers of confusing misinformation. Controlling information is Cipher’s most powerful weapon throughout the years, and is central to his many schemes. As it turns out, the information wasn’t really bogus so much as useless. The identities revealed to Snake were probably the members of the Wisemen’s Committee, the original alliance of American, Russian and Chinese contributors which amassed the Philosopher’s Legacy. This happened just after World War I… or about a hundred years before the events of Sons of Liberty. Historically interesting information, but totally unhelpful to Snake’s current situation. – Who is really in charge of The Patriots? Why are they so corrupt? As of Donald Anderson’s death in Metal Gear Solid, nobody. Dr. Strangelove began development of The Patriots AI in the 1980s, but she died before its completion. AI was Strangelove’s scientific superpower, so after her death no one else comes close to what she was able to accomplish. (This explains why her AI machines were so sophisticated in Peace Walker, while the Metal Gears in Guns of the Patriots moo and fall down a lot.) Major Zero continued development on the AI in its imperfect state, but he wasn’t able to oversee it either, since Skull Face had poisoned him and he spent the next 30-ish years slowly losing his mind. Zero mentions that Donald (aka SIGINT) was running a lot of the day-to-day tasks in one of his tapes in The Phantom Pain. And this was probably fine until Ocelot tortured him to death in Shadow Moses. From that point on, the AI was spinning without supervision, running the same processes over and over, causing trouble for everyone. Over the decades, random mutations in the AI’s subroutines ended up having a corrupting influence. The AI organized the S3 plan in Sons of Liberty and eventually invented the War Economy in Guns of the Patriots. – What is the S3 Plan, and what the hell happens at the end of Sons of Liberty? The last hour or so of Sons of Liberty is where Kojima intentionally went full-on batsplat banana sandwich on his players. The one-line summary of this 40-minute labyrinthine infodump is, “The Patriots AI went crazy.” The S3 Plan is the Mutant Crazy AI playing its hand at being Cipher. Solidus tells Raiden that S3 stands for “Solid Snake Simulation”, and he believes this to be true. The idea is The Patriots concocted a Shadow Moses-like live exercise to see if a green recruit with minimal combat experience could be turned into the next Solid Snake. It’s kind of a 21st century version of Les Enfants Terribles — instead of growing a new supersoldier from scratch as a clone, now we can make one on the fly with rudimentary VR training and extreme live fire. Solidus was fed bad information by The Patriots, however, and the AI explains to Raiden what S3 really is: Selection for Societal Sanity. The AI has decided that there is too much raw information out there, and wants to control the flow of it to such a degree that a person’s entire life can be fabricated around him. That’s what happens to Raiden: he’s given a fake girlfriend, a fake colonel, a fake Shadow Moses playground to kick around in, a fake FOXHOUND to join, etc. Virtually nothing Raiden believes to be true actually is, thanks to The Patriots running circles around him.  In other news, Raiden beat Quiet to full frontal by 14 years. Who does Revolver Ocelot work for? In Snake Eater Ocelot works for the CIA. After Snake Eater Ocelot works for Big Boss. Ocelot is the first of many characters who becomes absolutely infatuated with Big Boss. Even way back as Naked Snake, Big Boss has a sort of inspiring magnetism that made people want to follow him. This magnetism is so inexplicably powerful that even people who want to kill him — Quiet, Paz, countless soon-to-be-Fultoned nameless grunts, and of course Ocelot — end up seeking his approval. This overwhelming charisma is what makes him so special to The Boss, and so integral to Cipher and The Patriots. And Ocelot falls hard. He so badly wants senpai to notice him that, at one point in Snake Eater, he steals all of Snake’s food and eats it in an effort to be more like him. More tellingly, in an unguarded moment towards the end of the game, Ocelot insists he and Snake learn each other’s real names. This is perhaps the one moment in the entire saga where Ocelot is being purely genuine. After Big Boss is burned to death in Metal Gear 2 and his biomass is swept up by The Patriots, Ocelot makes it his life’s mission to recover the remains and destroy The Patriots. This isn’t sentimentality; Big Boss’s remains are the literal, physical key to locating The Patriots. At this point in time the AI still sees Ocelot as an especially valuable asset, so Ocelot is very careful to position himself without blowing his cover. At his most convoluted, Ocelot is four levels deep: Liquid doesn’t know he works for Solidus, who doesn’t know he works for The Patriots, who don’t know he works for Big Boss. The masterstroke here is that, on some level, Ocelot actually does work for Liquid and Solidus. They both want the same thing he does. If either of their crazy terrorism plans succeeds, he can end the charade and assist them directly. If they fail, he has just enough plausible deniability to maintain the ruse and bide his time. – So who or what is Liquid Ocelot? Ocelot, pretending to be Liquid Snake. There was a point when Liquid’s ghost arm was actually in partial control. During the cutscenes in Sons of Liberty where Liquid speaks through the arm, that is really Liquid and he is really taking over. This doesn’t sit well with Ocelot,0 so he has the arm removed and replaces it with a synthetic one. He doesn’t reveal his new robot arm until the end of Guns of the Patriots. According to Big Boss, Ocelot kept up the Liquid ruse by undergoing a treatment of drugs and nanomachines to trick his mind into believing he was Liquid Snake in a new body. (A similar process worked once before, in The Phantom Pain, to trick his mind into believing Venom Snake was the real Big Boss.) After Big Boss is burned to death in Metal Gear 2, Ocelot’s goal is to locate his body and bring down The Patriots. The AI doesn’t realize this, though, which is why it seems like Ocelot is a good little Patriots soldier all through Sons of Liberty. In that game, what comes across to the player is that Ocelot and Liquid’s ghost arm are working at cross purposes. We’re given an explanation for why Ocelot re-writes his brain during Big Boss’s exposition at the end of Guns of the Patriots: “in order to fool the System”. Becoming Liquid’s mental doppelganger allows Ocelot to actively work to destroy The Patriots without The Patriots twigging to his betrayal. The AI believes he’s Liquid and acts accordingly: by tapping Solid Snake and sending him to the battlefield. – How can Snake be part Japanese, if his parents are EVA and Big Boss? In the same conversation where EVA reveals she is Snake’s mother, she explains he was conceived via in vitro fertilization. The egg donor was a lab assistant of Dr. Clark, a character who is only ever identified as “a healthy Japanese woman”. Apparently, Vulcan Raven can sense the influence of healthy Japanese women even years after they’ve been murdered by Cyborg Ninjas. – How is REX still operable, and how is it a match for RAY? REX is the best Metal Gear ever built. It is the Cadillac of Metal Gear. It is an artisinal, home-brew Metal Gear whose secret ingredient is love. I keep mentioning this idea of a “scientific superpower”. Sometimes, a scientist in Metal Gear has such incredible aptitude for a field of study that their accomplishments and insights are presented as being literally unique. As in, if they die, their field dies with them, never to be replicated. There’s a good reason so many Metal Gear games start you off by sneaking into a base to rescue a scientist. Dr. Strangelove’s scientific superpower was developing AI. Naomi Hunter’s was the implementation of nanomachines. And Hal Emmerich’s is building Metal Gear. While REX is not as big as Sahelanthropus nor as versatile as RAY, it is the only Metal Gear model that displays human characteristics. Otacon speaks of REX as a person; he specificially designed it with a weakness to give it a certain je ne sais quoi. None of the Metal Gear superscientists like to see their creations destroyed, but Otacon actually takes it personally. To him it’s not, “Liquid has a really powerful battle tank,” but rather “Liquid stole my friend, who happens to be a powerful battle tank.” He takes it personally again, nine years later, when he realizes what Liquid Ocelot wants with its railgun. It’s this connection between a boy and his bestest battle tank buddy that accounts for REX’s ʜᴜᴍᴀɴ ᴇʟᴇᴍᴇɴᴛ. Otacon is so good at Metal Gear that you can cover REX in chaff, pelt it with stingers, carpet bomb it, leave it to rust for ten years in a wet Alaskan bunker, and all it takes to get it back up and running is a pep talk and some Street Fighter moves.  REX’s little brother is pretty awesome, too. I have another question? That’s not a question. – Okay but I have one anyway? Sure, leave it as a comment to this post and I’ll do what I can to write a follow-up someday. – Didn’t you do a bizarre and hilarious rap song about Ocelot? Yes. Yes I did. Thanks for reading! Fantasy Strike is a neat fighting game. If you’re ever in a position to try it out without having to buy it, I highly recommend it. You’ll have fun tinkering with it until the novelty wears off and you move on. And if you’re like me, your parting thought will be something like, “Shame there wasn’t more to it.” The game is still in Early Access, but all the characters are in and other than a 1P story mode it’s pretty much feature complete. What you see is what you get with this one. The crowdfunding is over, it’s made its way around the trade shows and fighting game tournaments, and the community it’s built is probably the community it’s going to have. Absent a miraculously successful marketing blitz on the full launch, I think Fantasy Strike has done all it’s gonna do. The concept of Fantasy Strike is wonderful. It was designed from the ground up by fighting game veteran David Sirlin to be as accessible as possible. The game is billed as being easy to pick up, but very challenging to master — appealing both to new players and tournament experts. There are two critical flaws that kill the game though, both stemming from mistaken assumptions on Sirlin’s part. And as much as I love the guy, Sirlin strikes me as being too stubborn to admit these mistakes, which would be the first step in correcting them and fixing Fantasy Strike. In this post, I’ll go into each of them in some detail. – First of all, I really love David Sirlin. There are very few game developers I’m a fanboy of. David Sirlin is one of them. He’s maintained a general game design blog for decades, and I’ve spent that time hanging on practically his every word. He’s got old design articles on every subject from the fun value of hidden collectibles in Donkey Kong Country to in-depth analysis about incorporating fun game bugs as standard features in remakes and sequels. I learned more about fighting games by reading his balance articles for Street Fighter II HD Remix than in all the combined time I’ve spent actually playing Street Fighter titles. I don’t actually own a lot of Sirlin’s games, outside of Fantasy Strike and his silly panda poker game, because most of what he designs are card battle games in the vein of Magic: The Gathering. This hasn’t dissuaded me from reading pages and pages of his analysis and design theory about card games, though, all of which I’ve found fascinating. So I know the man’s work, and I know something about his game design philosophy. I also know he has a stubborn streak that has resulted in some burned bridges across various internet communities. For example, when most reviewers were championing the decision to make the online edition of Street Fighter 3: Third Strike arcade perfect, Sirlin had the audacity to point out that the arcade version of Third Strike was kinda butts, and a re-balanced version would have made for a much better game*. He was totally right about this, and I was on his side every step of the way, but the manner in which he argued his points, dismissing out of hand that Third Strike fans with different priorities might have a valid argument, earned him no small amount of abuse. And it’s this stubborn streak, this sense of I’m right gosh durnit, why can’t everyone just see that, that I see in his responses to feedback Fantasy Strike has received. I find myself disagreeing with Sirlin on some key aspects of what Fantasy Strike is supposed to be, and what could make it great. *Third Strike had 19 playable characters, but at the highest competitive level only three could win fights. It was a boring meta both for competitors and spectators. Sirlin’s argument was that rebalancing the game to make more of the characters viable would increase depth and attract more players to the game. – Second of all, I’m a filthy casual. And this has the unfortunate side effect of Sirlin assuming I don’t exist. Fantasy Strike is billed as “the strategic fighting game for EVERYONE”, but what Sirlin really means by this is that he is targeting two kinds of players: expert fighters who will enjoy the game’s strategic depth, and newbie fighters who he hopes will speed through the learning stages to become experts. He’s not aiming at people who are neither experts, nor want to be. I’m standing here waving my hands around, and senpai is not noticing me. I approach a fighting game the way I approach any sort of game: I play it until I either finish it or it stops being fun, then I move on to the next game. I feel like 30-40 hours of playtime out of a $20 Steam game is pretty good value. The most I’ve played any fighting game is Super Street Fighter IV, where Steam says I have just shy of 100 hours logged. 100 hours is a long time for me to play a game, but it’s a fraction of a fraction of what is required to become an expert player, even in a game with single-button specials. – Accessibility is still an unsolved problem. This is the first of Sirlin’s misconceptions: he thinks people quit playing fighting games — or avoid getting into them in the first place — because the moves are too hard to do. In his mind the barrier to entry is the controller, the physical interface between player and game, and if you can just push through that you can begin what he calls “actually playing”. You’re not spending brain cycles on whether you can physically perform a move, but rather should you perform it. If you read the HD Remix articles I linked earlier, you will see him repeat this phrasing again and again. It’s easy to see why Sirlin thinks this. He learned to play fighting games in the Bad Old Days, when Capcom and SNK arcades ruled the roost. In those days the special moves really were difficult to do. You were lucky if the specials were listed on a cabinet decal or instruction manual, and even then, the motions were notoriously finnicky. I bet Sirlin spent a lot of time back in the ’90s fumbling with bad control schemes before he got güd, and those memories were probably front and center when he drafted the Fantasy Strike design doc. But this is a solved problem. Sirlin himself implemented many of the solutions in his work on HD Remix: he widened input windows, relaxed directional requirements, and reduced button mashing. These changes are a big reason why HD Remix is my favorite iteration of Street Fighter II — I can do a dragon punch now! What he didn’t realize, though, is that every other modern fighting game has adopted this design philosophy. The motions for specials in Street Fighter IV are even more lenient than HD Remix; nobody has quit playing that game because they can’t throw a fireball. This design trend probably started with Super Smash Bros., where every move is as simple as “button plus direction”. The Bad Old Days are gone. The real barrier to entry is the competition, not the controller. It’s when you haven’t yet learned enough to make good decisions, nor developed the muscle memory to implement those decisions. It’s true that Fantasy Strike gets you to that point faster than Street Fighter does, maybe a couple hours versus a couple days. But it still has combos to master, matchups to learn, and frame data to study. Jaina’s fireball being on a single button rather than QCF isn’t very helpful when what you really need is the knowledge that Geiger’s move has a long recovery, the presence of mind to recognize the situation, and the muscle memory to react quickly enough to make that fireball count. In a world where everyone is having trouble driving stick on icy roads, Sirlin is patting himself on the back for implementing push button ignition. – Babby’s First Fighting Game Being the Sirlin fanboy I am, and seeing his previous work on HD Remix, I have full confidence that Fantasy Strike is a deep, well-balanced and strategically interesting game. As we’ve established, though, that’s not really what I’m in the market for. The players he needs to sell that line to are the established fighting game community, and by most accounts they’re not buying it. Part of this just comes from the man himself being such a polarizing personality for such a long time in established fighting game circles. There are lots of people out there who don’t like Sirlin, for one reason or another, and just won’t buy his game no matter how good it is. That leaves two other places to potentially cultivate interest: veteran players who are intrigued by what Fantasy Strike has to offer, and veteran players who don’t have a game to play. We can discount the second group pretty much immediately. If you’re a fighting game veteran, you already have a game to play. You’re not going to move from that game to Fantasy Strike unless it becomes a blockbuster smash, and it’s not doing that. To the remaining fighting game veterans, Fantasy Strike is a hard sell. If you have what it takes to climb the ranked ladders, you are not concerned about accessibility. The idea that the hard part of fighting games are the QCFs must sound absurd to, say, the 98th best Blanka in North America. The #1 selling point fails to land, and I really don’t know that Fantasy Strike has a #2 selling point. Passed all that, though, even veterans who want to actively support Fantasy Strike are going to have a hard time doing so, because nobody is playing it. steamcharts.org lists Fantasy Strike as having an average user base in the single digits. Contrast that with Skullgirls, an indie-developed fighter that’s been out for several years, but has cultivated a dedicated playerbase by leveraging unique gameplay features. In terms of active playerbase Fantasy Strike is more in the neighborhood of Divekick, and that’s not a good look. – So why doesn’t Brickroad like it? Okay, the game’s not appealing to newbie players looking for an easy in, and it’s not appealing to veteran players who want a new playfield. I’ve already established I’m not in either of those groups, so why doesn’t Fantasy Strike appeal to me? There are no online lobbies. And there never will be. My usual rule regarding Early Access titles is not to buy them unless I’m happy with the state the game is currently in. I broke this rule with Fantasy Strike for three reasons. First, the game looked cool and colorful and fun. Second, I was very happy Sirlin had finally developed a video game I was interested in playing rather than simply reading design articles about. And third, I was absolutely certain online lobbies would be added to the game. If you’re not familiar with lobbies in online fighting games, here’s how they work. You open a room and invite a bunch of friends. The game then matches two of you up while the rest spectate the match. The winner of the fight moves on to the next match and the loser goes to the back of the list. It’s a way for a group of people to all play the same two-player game together. This feature is an industry standard. The only major series I’m aware of without lobbies is Super Smash Bros., but those games have 4-player simultaneous play, which is functionally the same thing. Lobbies are important to me as a player because fighting games are stressful to play, even with a group of friends at about my skill level. I much prefer playing a few matches at a time to grinding out an endless row of them. I really like playing as hard as I can while I’m on a win streak, but once I lose I appreciate being able to take a break and spectate. Lobbies are important to me as a Twitch streamer, too, because it makes for the best viewing experience. Viewers are either watching my match and listening to my friends commentate on it, or they’re watching the same match I’m spectating and listening to me commentate for my friends. It also makes it easy for viewers to get matches with me, without either of us having to screw with our friends list or manually send invites. So when I learned online lobbies was not a feature Fantasy Strike was ever going to have, I immediately regretted my purchase. Here’s Sirlin’s response on the Fantasy Strike forums when asked about it:

This reveals the second mistaken assumption Sirlin has: that Quick Match is the best way to play fighting games online, to the exclusion of all other possible ways to play. (I don’t know what the comment about Hearthstone is supposed to mean. It seems weird he’d conflate two entirely different genres of competitive game like this.) Again, I can follow his logic here. Quick Match is the default method of playing for experts and for people trying to be experts. The way it works is you push a button, and some guy in Germany pushes a button, and then the game throws the two of you into a match. The loser is given an option to rematch, and then both of you are dropped back into the queue so you’re available for the next guy who pushes a button. Notice, though, that the only other way to play Fantasy Strike is to challenge someone on your friends list. When you do this you are locked into an endless series of matches with that friend until one of you decides to leave. Fantasy Strike makes it easy to play with randos, and it makes it easy to play with a single friend, but there’s no easy way to play with four friends at once, or to make yourself available to a small group of people who happen to be watching and want to jump in. I know from experience that trying to organize a Fight Night in a game using just these features is a major hassle, and my solution in the end was to stop playing that game. If you’re looking for a steady stream of competition, Quick Match is your jam. And if you want to spar against one person, the single button invite is an elegant solution. But if you want a fun, casual night with a couple friends on Discord chat, Fantasy Strike can’t really accomodate you. Sirlin is very, very wrong when he says “custom rooms take away from Quick Match”. The two game modes appeal to very different kinds of players, and it’s his own tunnel vision that prevents him from seeing that. In his mind there is one particular correct way to play his game, and he won’t spend development resources on a feature that allows people like me to play it wrong. So, unfortunately, I’m just going to stop playing it altogether. Which, yeah, is really a shame. – I wonder if David Sirlin is the type of guy who Googles himself. If so, I just want to say I’m still a big fan. Thank you for Playing to Win, and for fixing Chess, and for giving T. Hawk that hilarious throw whiff animation. I want you to know I think it’s a travesty that HD Remix and Puzzle Fighter aren’t in that big Street Fighter collection that’s coming out. I urge you to reconsider your decision to leave out the one standard gameplay feature that would enable me to enjoy your game. Even if you don’t, I hope Fantasy Strike eventually finds its audience and that you get what you want out of it. I’m still following the game on Twitch.tv, for what that’s worth. And to everyone else, thanks for reading! There are lots of carefully-codified rules in Dungeons & Dragons for awarding experience points (XP) for combat encounters, but the material is pretty loosey-goosey about rewards for roleplaying encounters. Here’s what I came up with for Flumphscape, my 5e Planescape campaign that ran for two years. My players were level 17 at the end of the campaign, and I estimate about half of their total XP was from roleplaying, using these variant rules. Maybe they’ll work in your campaign? We’ll see! – Goals I had a few goals in mind when I designed the rules for blips.