Years ago I wrote this blog post summarizing the process of making a YouTube LP series. Recently I was asked by a Twitch viewer if I’d make a video about the process. I don’t think it’d make for an interesting video (plus capturing and editing hours of Photoshop footage doesn’t sound fun), so I’m writing this blog post instead. Since making this content is now my job, and I make so many vague allusions to “doing video work”, it’s probably a good idea to lay out exactly where all your money is going!

•

Step 1: Pick a game.

You’d think this would be the easiest part of the process, but it’s actually a bit trickier than it seems. It’s certainly trickier than it was back in 2010, when the theme of my YouTube channel was “games I loved in the 90s”, and I hadn’t already LP’d those yet. Not every game I love has the makings of a good YouTube series.

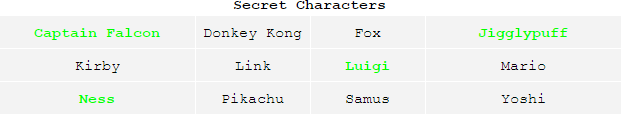

This time, the decision didn’t fall to me. My $50 Patreon reward is an LP series of your choosing, with the caveat that I don’t guarantee to like the game or say nice things about it. (See also: Sonic Adventure 2.) The chosen game was Ori and the Blind Forest, and I made sure to keep careful notes about my LP process.

Is Ori a good game for a YouTube series? I’d say yes. The game isn’t too long, there are lots of varied challenges, and the story is thick and meaty without getting boring. These are all qualities that make a game fun to watch for people who aren’t already familiar with it. The game has a lot going for it, but also some pretty deep flaws, which makes for interesting commentary. And, gosh, but it’s pretty!

Is Ori something I’d have picked myself? That’s a tougher question, and you’ll just have to wait for the live series for a detailed answer!

•

Step 2: Do a test play.

This is a super-important step that I’m very careful not to skip anymore. The idea is I want to have a good working understanding of the game in my head before I sit down to record. With few exceptions, blind recordings tend to end in disaster, and are to be avoided. Besides, viewers that like to watch the salty frustration of a blind run can always drop my my Twitch stream.

Even short games that I’ve played a million times, such as Raiders of the Lost Ark, benefit from a test play. Oftentimes games I remember as being short and breezy turn out longer and more difficult than I remember, and I have to adjust. Or I’ll have forgotten some obscure thing in the game, and it’s better to discover it now than to spend four videos searching for it.

Maybe most importantly, though, is a test play allows me to take notes about the game that turn into talking points during recording. A lot of the observations and stories you hear during a typical series are chosen ahead of time.

In the case of Ori, since I hadn’t played the game before, I decided to stream my test play. The first run of the game was pretty rocky, but it provided enough clarity to learn the game pretty well on my second test run. So before I even pushed the record button for the first time, I had already invested a good deal of time into my Ori series:

•

Step 3: Record!

The recording process is pretty much what you’d expect: boot up the game and play it with the recorders running.

For console games plugged into my capture card, I do my recording with OBS Studio. For anything else, I use Bandicam. Both of these programs are capable of recording lossless footage, which for an HD game like Ori means 50 gigabytes of raw video to sift through.

I record audio using Audacity, a program so good I can’t beleive it’s free to use.

Test recordings are as important to the process as test plays, and are another important step I make sure to never skip. There are a multitude of audio and video options I have to constantly be tweaking as I go back and forth between recording footage, streaming to Twitch, and using my PC for personal stuff. All it takes is for one box to be unchecked, and a whole session is junked. So before each session I do three quick tests: a Bandicam/OBS test to make sure the game is being recorded at the proper resolution and framerate, and to ensure the audio is coming through; an Audacity test to make sure my microphone is configured properly; and one or two minutes of the two combined.

All recording sessions require a sync point, where I know the audio and video are matched up properly. This is easy to do. I start Audacity first and say “Now!” right when I hit the record button in Bandicam. That way all I have to do is line up the beginning of the video file with the big bright spot in the audio waveform, and I’m good to go.

I try to keep recording sessions between one and two hours. Shorter sessions are more difficult to divide into YouTube-friendly chunks. Longer sessions run the risk of being ruined by corruption, crashes, or interruptions. Nothing’s worse than losing video from a game that auto-saves and keeps only one save slot. (We experienced a brown-out during my recording of Octodad: Dadliest Catch, and I had to play the whole game again from the beginning to salvage my save!)

You can tell where these recording sessions begin and end while watching one of my playlists if the first words out of my mouth are something like “Welcome back!”

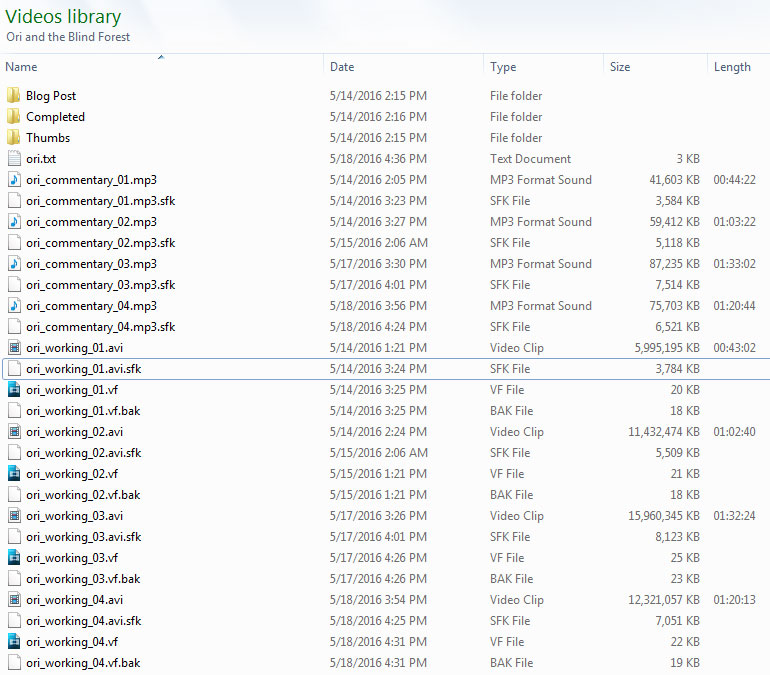

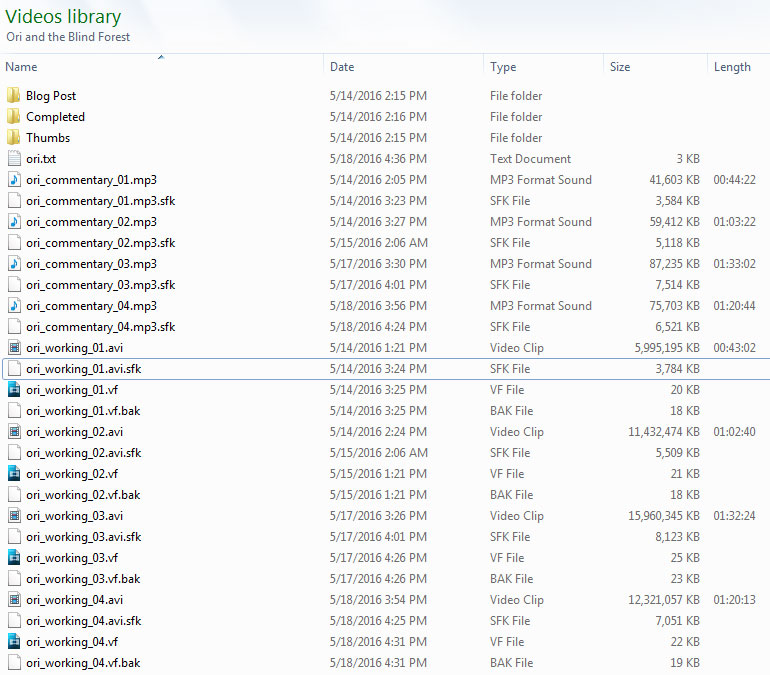

Ori consists of three major game areas, plus a prologue/tutorial section, so I recorded it in four parts ranging from 45 to 90 minutes. Then I load up Sony Movie Studio to line everything up and make sure the volume levels sound nice. With that done the Ori directory in my LP folder looked something like this:

Most of these files are temporary, and get deleted once the LP is finished and sent off into my archives.

•

Step 4: Chop up the footage.

Somewhere back in pre-history YouTube had a strict 11-minute limit on videos. That limit was later raised to 16 minutes, and later still the time limit reserved as a penalty for channels who either weren’t properly confirmed or weren’t in good standing with YouTube’s TOS. My channel is confirmed and in good standing, so I can (and sometimes do) upload long videos, but I find the sweet spot to be between 15 and 20 minutes.

To calculate how many chunks each sessions should be divided into I keep a helpful calculator bookmarked: Time Calculator at ScottSeverance.us. This process requires a bit of tweaking and a bit of eyeballing, since I don’t want to chop up a sentence or a thought.

(That sometimes happens anyway, and viewers leave me comments like “Argh! Cliffhanger!” These cliffhangers are never done intentionally, but there’s value in them since, once in a while, it gives viewers a really good reason to want to see the next episode.)

With everything chopped up, I now know how many videos are in the series.

•

Step 5: Prep the txt.

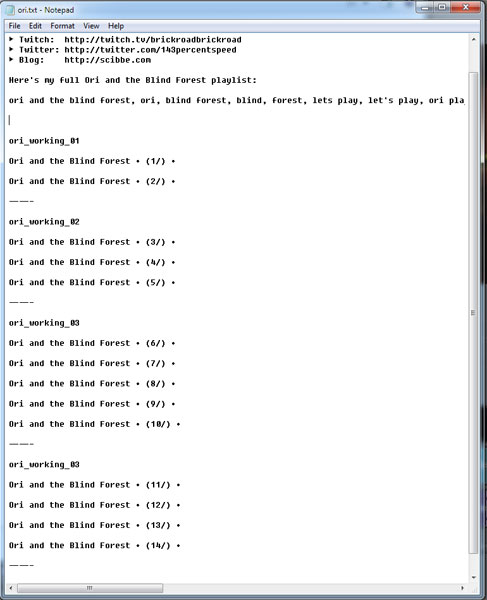

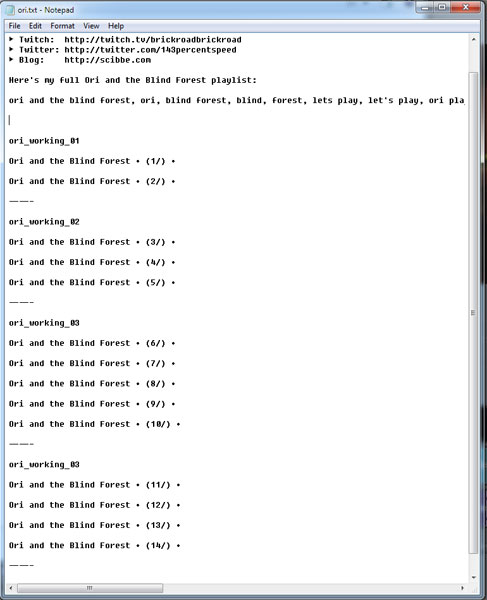

Each series has a text file filled with notes that mostly get copied over into YouTube descriptions later. As soon as I know how many videos are in the series, I go ahead and prep the text file, like so:

Each entry on the list is filled in later with titles and video descriptions. I also keep post-rendering instructions in this file, such as special rendering or annotation instructions, and the eventual URL of the uploaded video. Since I have to reference this file in order to make the video live, it’ll make sure I don’t miss anything down the road.

For example, in one episode of Ori I mention this blog post. When I go to make that video public some number of months from now, I have a helpful note saying “Don’t forget to put the blog post in the description!”

•

Step 6: Make YouTube thumbnails.

If I may editorialize a moment, I really hate the practice of making hundreds of identical YouTube thumbnails. A lot of channels have this pseudo-lazy practice, where their channel branding includes a single homogenized look for their thumbnails, so browsing their channel means looking at a hundred identical orange rectangles, or a hundred identical copies of the channel owner making a silly face. I say “pseudo-lazy”, because the lazier practice would just be to select one of the frames YouTube selects for your video, and go with that as the thumbnail. For years that was my preferred practice because at least then you can glance at the thumbnail and get an idea about what the video contains.

That said, there is some value to having some channel branding or information in the video thumbnail itself, to catch someone’s eye as it wanders down a list of same-y videos. My compromise is to superimpose the game’s title and episode number on a still frame from the video.

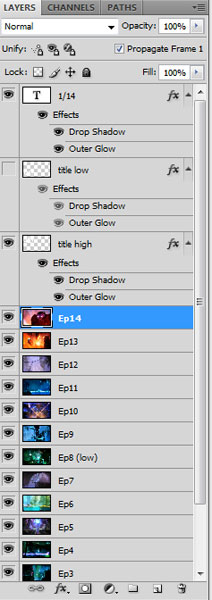

Movie Studio has a handy “take a screenshot of this frame” button, so I do that once for each episode, and stack them up into Photoshop layers. That looks something like this:

There are “title high” and “title low” layers because sometimes the interesting part of the thumbnail is in the top corner, and sometimes it’s in the bottom corner. The episode number can’t be moved to the bottom corner because YouTube automatically sticks the video length there, which sometimes makes the text there unreadable.

•

Step 7: Snippets!

Each video in a series ends with annotation links to the previous and next episodes, so those need to be made before I can render anything. I call these “snippets”.

To make the snippets, I just look for fifteen interesting seconds from each episode, chop them out of the main video, and strip the audio. After rendering these out, I have a snippet from each episode.

•

Step 8: Mock up an outro layout.

Next I have to make the outro, the part of the video with the Subscribe! and Patreon links. In pixel games, such as Clash at Demonhead, I can make a nice-looking static layout to stick everything on. For HD games like Ori, though, I lack the graphical aptitude to make a nice-looking layout. Instead, I’ll take a 16-second video clip of something kind of laid back from the game that I don’t think people will get tired of looking at video after video.

For Ori I chose some footage of Ori frollicking around a nice serene lake. In order to make sure everything looks nice I load a screenshot of my footage into Photoshop along with some contrast-y leftover shots from when I made the thumbnails, then play around with fonts and positioning until I have something like this:

Using the mockup as a template, I can make all the outro overlays I need. Ori’s overlays are pretty simple: a dry brush font and drop shadows for the snippets. After a little noodling with the template I have as many outro overlays as I do videos to put them on; one for every Patreon supporter who gets a shoutout in that series. Which brings us to…

•

Step 9: Record shoutouts.

…recording shoutouts! This is one of my least favorite parts of the process, just because I feel silly sitting in front of the microphone saying the same sentence over and over again.

Of course, before I can record these shoutouts or finalize the outro overlays, I need to know which of my handsome and intelligent patrons is getting a shoutout for each video. For that I keep a spreadsheet of all my patrons and which LPs they’ve received shoutouts in. I compare my spreadsheet to the list in my Patreon account, making edits as needed. Once you get a shoutout, you don’t get another one until everyone’s gotten one.

I let random.org do most of the work here, although I might re-roll if someone ends up getting two shoutouts in back-to-back series. Due to the way my upload schedule works, though, that ends up not mattering all the time. I think there’s one instance in my upload history where someone got a shoutout two days in a row, because a freshly-recorded series was being uploaded alongside one that’d been recorded months ago!

•

Step 10: Scour the footage, and take notes.

This here’s my least favorite part of the whole process, because it’s boring and time-consuming. I watch every second of every video to make sure there aren’t any issues in the final product. This is my last chance to fix desynced audio, corrupted video, bleep out naughty words that slipped through, and so on. As I watch, I make a list of funny or interesting things that happen, so I can write a description and video title.

You would think this would take exactly as much time as recording, but it actually takes a bit longer. Since my work computer isn’t quite beefy enough to watch HD video in the Movie Studio preview window, lots of pausing is necessary to make sure I actually see the whole video, rather than just let it lag out.

•

Step 11: Plug in the outro.

The last thing that needs to be done before I can call it a video is stick the outro in place. This involves layering the overlay I made on top of the snippets on top of the outro footage, then fading the episode into it. That looks like this:

The process of lining all that up to look nice in Movie Studio takes a little while, but once it’s done I can save a preset so subsequent episodes only require a click or two. That done, the video has a nice attractive outro for all my viewers to skip!

•

Step 12: Render!

The most time-consuming step, in terms of minutes-per-episode, is rendering the file. Turning the raw footage into 720p 60fps .mp4 optimized for YouTube takes about 45 minutes, and it can be difficult to multitask since things can go awry if I don’t babysit. More than once I’ve set the computer to render a file, only to come back an hour later and find it ran into a weird error and needs to start over. Grr!

Most rendering is done on the work PC, leaving the gaming PC free. Sometimes I’ll use the time to test play the next series, or do some D&D planning, or maybe stream, but usually I just queue up something on Netflix to kill the time. I’m terrible at multitasking, so if I get too involved with another task I’ll fall behind on my rendering.

•

Step 13: Upload and annotate.

Once the watching and rendering is done, I have a pile of finished .mp4 files ready for YouTube! I back these up on two hard drives, and in most cases they just sit there until the morning of the day I upload it. In the case of a patron’s LP, like Ori, I instead upload each episode as I finish rendering and save them to an unlisted playlist. In either case, the annotations get added when the video goes live for public viewing.

(Insert long rant about how much I hate YouTube’s annotation interface here!)

•

And that’s the process! Start to finish, Ori took just over 38 hours to complete, 14 of which were test plays, and 11 of which was rendering time. Just about a full-time work week, when all is said and done.

Thanks for reading!

The Sigilian Calendar

My new D&D 5e game is a Planescape campaign, and I’ve decided to set quite a lot of it in Sigil. Weirdly, none of the official material includes a Sigilian calendar, so I thought I’d take a crack at making my own. The way I figure it, there’s no way the Fraternity of Order hasn’t found a way to mark the passing of days and months. I also figure a significant portion of Sigil’s population has no use of any sort of calendar, and just ignores it. In any case, here’s what I’ve come up with.

A messy example of the calendar can be seen here.

—

Days of the Week

Just like here on Earth, there are seven days in a week. They’re named after the various wards of Sigil. At one time in Sigil’s history each day had a particular meaning or purpose, but now they all mostly blur together. Some traditionalists grumble about that.

Lady’s Day – A day of rest for Sigil’s government, the Court is closed on Lady’s Day. Many Guvner-owned places of business all over town are dark as well. Prison operations used to be suspended on Lady’s Day as well, but since the current Mercykillers factol took charge, they’re open for “business” 24/7. Superstitious folks are extra careful not to raise the Lady of Pain’s ire on this day.

Low Day – The second day of the week used to be reserved for special projects at the Foundry and other forges scattered throughout Sigil. In fact, there used to be a city ordinance (the Sigilian Smog Reduction Initiative) that limited smoke-producing works to three days each week, beginning with Low Day. The unpopular legislation was nixed once it started to adversely affect Sigil’s economy.

Clerk’s Day – Traditionally, Clerk’s Day was the one day a week where attendance was mandatory for all employees of Sigil’s beaurocracy, in an effort to ensure one day each week where taxation paperwork, licenses, records requests and the like were more expedient. This only resulted in said beaurocrats finding any number of loopholes, however, and now the rule is only loosely enforced.

Guild Day – The middle day of the week is traditionally a good time for the movers and shakers in Sigil’s various guilds and businesses to hold meetings and make all sorts of deals. Agreeing to meet to discuss and finalize a business deal on Guild Day is considered a sign of respect. Offering to meet on any other day might be met with suspicion or disdain by old cutters who remember the way things used to be done.

Hive Day – Every few cycles some berk gets it into his head to single out Hive Day for some kind of long form civil works project; cleaning up The Ditch, rounding up the more seedy Collectors, mobilizing Sigil’s upper crust to volunteer work for the downtrodden, that sort of thing. Even the legally-sanctioned attempts die pretty quick, as their organizers drive themselves barmy trying to impose any sort of order on The Hive.

Market Day – There’re a half million rules and restrictions and quirks of law about who can sell what in the Great Bazaar, and on paper lots of these rules are relaxed each Market Day. In practice, it’s rare for anyone to follow or enforce any of these, unless the Hardheads really have it in for one particular merchant. Lots of informal Indep gatherings do tend to happen on Market Day, though.

Ring Day – The last day of the week symbolizes Sigil as a singular unity, rather than any single ward. It’s the closest thing to a weekend the City of Doors has. Many of the city’s temples recognize Ring Day as a day of worship. Lots of galas and parties happen on Ring Day amongst Sigil’s upper classes, considering most of those bashers have the following day off work.

—

Astral Days

Eons ago it was theorized that the Astral Plane “cycled” across each of the planes it touched, and that this connection moved once per Sigilian cycle. Seventeen days, one for each of the Outer Planes, then one for the Prime Material. Every nineteenth day the Astral’s connection was strongest in Sigil itself, and so those days were declared Astral Days. Of course, the whole business with cycling Astral connections are pure screed, but the tradition stuck.

Every nineteenth day in Sigil is an Astral Day, and these days don’t belong to any week or month. This creates cases where, for example, Lady’s Day doesn’t directly follow Ring Day. Those weeks tend to be particularly raucous. This means that just about every third week has eight days instead of seven. Some folks like to think of the collection of Astral Days as a short month whose days are spread throughout the year instead of coming all together at once.

The official faction of the Astral Days is the Athar. The faction tends to increase its proselytize a big more during Astral Days, and many cagers consider it taboo to worship their powers or enter a temple on these days.

—

Dabusdan

The last day of the year is Dabusdan, and is considered to be separate from any month, although it still falls on a day of the week. It’s the one day a year the dabus do no work in Sigil. In fact, it’s very rare to see one out and about on this day. Since it occurs so regularly (once every 368 days), it’s a good way to mark the end of one cycle and the beginning of the next.

—

Ethil Rué

Halfway through each cycle, the calendar is interrupted for two weeks connected with the Inner Planes. Each week includes one day for an Energy Plane, one day for each of the four Elemental Planes, and two days for the Ethereal. These two weeks prove exceptionally busy for the Bazaar, as merchant princes from the Inner Planes come flooding in with their exotic goods.

The first week (known formally as Ethil Rué Fulaan) begins with a day called Life, marking the Positive Energy Plane. The second week (Ethil Rué Rufaan) begins with Death, marking the Negative Energy. To further confuse things, the Earth and Air days switch positions during the second week. This gives official recognition to every possible Para- and Quasi-Elemental Plane, although nobody but the Guvners particularly cares.

If an Astral Day happens to fall in between two Elemental Days (which only occurs once every few years) an offshoot of the Sensates takes it as a sign and puts on a marvelous celebration of the Para-Elemental Plane that results from the combination. This can be fun when it’s Ice’s turn, what with the sledding and snow cones. People are less enthusiastic about Magma, Smoke or Ooze’s celebration, though.

Death, the first day of Ethil Rué Rufaan, is the official day of the Dustmen, although they don’t do anything special. The Doomguard are the official faction of Ethil Rué Rufaan in total. The Godsmen were assigned to Ethil Rué Fulaan, but they have unofficially abandoned it in favor of an entire month elsewhere.

—

Months of the Cycle

Each Sigilian cycle includes nine months. Four months have 36 days, four have 38, and one (the center month) has 40. The months correspond with the nine alignments, and are named for powerful members of each exemplar race of the Outer Planes. In addition, each month has an official faction. Some factions take their assignments seriously, planning city-wide events and celebrations during their time. Others could care less.

It’s thought that long ago the nine months were much more strongly connected to the outer planes they represented, and Sigil’s overall mood would gravitate in that direction. That’s not the case anymore, if in fact it ever was, but tradition still holds that each month is the best time of year for different kinds of business and actions. Others say that the personalities of those born in Sigil is determined by the month in which they’re born.

Amnizuus – Named for the Amnizu, stewards of the fifth layer of Baator, Amnizuus is also called the “Blood Month”. It has 36 days, and is considered to be a good time in Sigil to make strategic decisions regarding bargaining and warfare. The Blood War tends to spill into the streets a little more during this time, although the fiends tend to behave themselves more often than not. The Blood Month’s faction is the Mercykillers, and the moniker suits them just fine.

Quintember – Named for the Quinton, the Modron record keepers of Mechanus. 38 days long, Sigilians also know it as the “Metal Month”. It’s known to be a good time to undertake long-term planning, or to break ground on new construction projects. Not surprisingly, Quintember’s faction is the Fraternity of Order. Guvner appointments and term limits begin and expire in this month. Most years a splinter group of Guvners appeal to move Quintember to be the first month of the year, rather than the second, to more neatly correspond with the new cycle, but this motion always meets with strong opposition from even inside the faction.

Toma – Named for the hawk-headed Tome Archons of Mount Celestia, the 36 days of Toma are seen as a time for self-improvement and honing of raw physical strength. Sigilians also know it as the “Light Month”, and the three lawful factions traditionally keep their lanterns lit throughout Toma’s nights in recognition. Officially, the month of Toma belongs to the Harmonium. Patrols tend to be larger and tighter during the month, as the Hardheads take great pride in keeping things especially in line when they have the spotlight. This also means recruitment efforts are redoubled during Toma; good news for those looking to join — or infiltrate — the faction.

Ursina – Ursina has 38 days and is named for the philosophical bear-folk of the Guardinals, the Ursinals. Its connection with the plane of Elysium makes Ursina a good month for charity and good works, but also for relaxation and introspection; lots of Sigilians take their holiday during Ursina. Elysium’s connection to the River Oceanus have led Sigilians refer to Ursina as the “Water Month”. The official faction, the Ciphers, have latched onto this symbolism to better illustrate their fluid connection between thought and action.

Cuprilember – At 40 days, Cuprilember (or the “Spire Month”) is the longest month of the year. It is split in half, however, by Ethil Rué, and so is often referenced as “early Spire” or “late Spire”. It’s named for the Cuprilarchs, a subrace of the enigmatic Rilmani known for brash acts of violence in their quest to uphold some cosmic balance. Being the center month, and having no month representing their home plane, Cuprilember has been adopted by the Signers. Jokes abound that having the longest month sooths their fragile egos. In addition, having no month of their own, the Indeps have unofficially claimed Spire Month for themselves, as well. (That is, those among them who care enough about such things.)

Arcanuus – 38-day Arcanuus has an interesting history. Originally it was tied to the Grey Waste and assigned to the Bleakers, who (predictably) didn’t much care about the appointment. At the time the Fated were trying to get their home plane of Ysgard recognized in the calendar, with no success. Instead of fight an eternal losing battle, the Fated seized Arcanuus for themselves instead, and embarked on a lifelong campaign to change its dreary connotations. Named for the Arcanoloths, the month’s new identity was strongly associated with arcane study, and now is known in Sigil as the “Arcane Month”.

Marlithuus – Originally called the “Dread Month”, Marlithuus is associated with the Abyss and is named after those terrible seven-armed demons, the Marilith. Originally no faction wanted to be associated with it, but the Bleakers have been stuck here ever since the Fated grabbed Arcanuus from them. Not content with having such a horrible month in every year, the Sensates, Godsmen, Signers and a few Ciphers were able to re-cast the month’s selfishly chaotic bent into a celebration of the creative arts. Nowadays it’s known as the “Song Month”, although that doesn’t keep some barmies from filling its 36 days with violence.

Graalember – The Slaad don’t have fancy names for themselves, only colors, and there is a lot of debate amongst greybeards over whether Graalember is named for the Grey or Green variety. Most folks find the confusion caused by the name to be the perfect fit for the month associated with Limbo. Officially the month is the domain of the Xoasitects, but they don’t recognize being tied down to one particular box. Instead, the Godsmen have unofficially taken the month for themselves, indulging in the pure joy of creation made possible by the most chaotic of planes. Also known as the “Shape Month”, Graalember is 38 days long and is associated with luck and psionics.

Ghaela – The last month of the year, 36-day-long Ghaela, is named for Arborea’s Ghaele Eladrin, warriors of compassion and protectors of the innocent. Most people in Sigil, however, know it as “Wine Month” and look forward to the many end-of-cycle parties thrown by the Sensates. Ghaela is known throughout Sigil as a time of brotherhood and good cheer. Or, at least, slightly less dismal cheer.

—

Sigilian Holidays

The number of holidays and special events in Sigil is infinite, but there are a few traditional days, many of which are faction-sponsored, that make it onto just about everyone’s calendar.

New Cycle’s Dawn (Amnizuus 1) – The first day of the cycle is a popular time for parties in all of Sigil’s social classes, from the snobbish galas of the Lady’s Ward all the way down to the fervid debauchery of the Hive. A tradition amongst Sigilian children is to keep count of fiends walking the street on the first day of the Blood Month; whomever spots the most gets a special treat during the evening’s festivities.

Green Beer Day (Amnizuus 9) – An old Spinagon named Rakakkukan has lived in a tiny kip in the Lower Ward for as long as anyone can remember, and just about as long he has been Sigil’s benefactor on Green Beer Day. Every Amnizuus 9, precisely at peak, the lights go on in Rakakkukan’s kip and he begins rolling cask after cask of powerful Baatorian ale out into the street, free to anyone who brings their own cup. The old devil’s reasons for this uncharacteristic charity have never been identified, and makes a lot of folks uneasy, but the bubbers line up year after year all the same.

Wyrm’s Day (day after the first Astral Day in Amnizuus) – The only “holiday” sponsored by the Mercykillers, Wyrm’s Day is a favorite amongst Sigil’s lower classes who just want to see a bit of gore. Traditionally the Mercykillers do a bit of housekeeping in the Prison on this day, offering pardons or executions to large numbers of long-time prisoners. As of late there have been far more of the latter, making for particularly grisly and memorable Wyrm’s Days.

Hashkar’s Address (Quintember 1) – Every year on the first day of the Metal Month the factol of the Guvners publicly addresses the people of Sigil in a very long, very boring speech. A huge variety of topics are discussed, mostly involving the state of Sigil during the previous cycle, and plans for improvement in the upcoming cycle. The speech tends to go far longer than anyone can stand to listen, with the record stretching just past 15 straight hours of Hashkar’s droning, methodical voice.

Forum of Law and Order (Quintember 2) – In theory the Hall of Speakers is available for anyone with enough jink and an opinion to rent out, but traditionally the Signers hand this one day over to Sigil’s triumvirate of law: the Guvners, Hardheads and Mercykillers. (No doubt for a very large fee!) Nobody else gets the floor on this day, and lots of lively debate ensues about the proper application of Sigil’s laws and the enforcement and punishment thereof.

Day of Civil Judgment (last Lady’s Day of Quintember) – While the courts are usually closed on Lady’s Day, an exception is made for this holiday, where the factol of the Guvners himself sits the bench for 24 straight hours hearing grievances. The regular court schedule is wiped clean for the day, and citizens are heard on a first-come, first-serve basis, no matter how petty or delusional their cases may be. On this one day only is the factol entrusted with final authority to hand down judgments without slowly grinding through the usual channels. For many Sigilians, this is their only shot at justice in civil matters.

Toma’s Resolution (Toma 1) – The first day of Toma, a month of betterment and self-improvement, it is customary to make resolutions on how one will make oneself better throughout the remainder of the cycle. Popular resolutions include weight loss, persuing a new profession, and finally hopping a portal out of this miserable place and setting up kip elsewhere ont he planes.

Toma’s Regret (Toma 2) – An inevitable favorite throughout Sigil, Toma 2 is an unofficial, tongue-in-cheek way to celebrate all the short-lived resolutions made the day before. Usually with lots of drink.

Good King Garfareon’s Name Day (Toma 21) – Sigil’s not the type of place where a high-up’s name day is likely to get much recognition, but an exception is made for Garfareon, ruler of whatever kingdom the Harmonium originally hailed from, on whatever Prime Material world that was. While it’s an official holiday and the Hardheads take it very seriously, most everyone else celebrates by rolling their eyes and making fun of the good king’s silly name.

Deva’s Day (Toma 35-36) Towards the end of the Light Month a venue is chosen — usually in the Lady’s Ward — for a large gathering of celestials to come together on neutral ground and share the past cycle’s triumphs and experiences. Bloods from all over the Upper Planes turn up for the two-day event. The first day consists of more formal meetings, discussion of business, peaceful resolution of conflicts, what have you. That all taken care of, the second day is spent socializing and partaking of good-aligned brotherhood of all flavors.

The Grand Games (first full week of Ursina with an Astral Day) – This eight-day-long event is sponsored by the Ciphers and takes over the entire Gymnasium and much of the surrounding area. The days are filled with formal athletics competitions and games of skill, and is the most organized most folks ever see the Ciphers get. Registration is open to anyone who wishes to compete, but only those with the most brutal training regimens have a shot at a medal. Despite the Ciphers’ best efforts to combat the seedier elements of gamesmanship, the Grand Games are the most popular gambling event of the cycle.

Prime Appreciation Day (first Ring Day of Cuprilember) – An official Sigilian holiday no doubt proposed by some greybeard who was kept awake at night by the Prime Material Plane not being recognized anywhere in the city’s calendar, Prime Appreciation Day is considered a joke by the best cutters and an excuse to torment Clueless by the worst. Currently no faction sponsors any events on this day, and by the time most Primes learn the ropes well enough to realize they have a day, they don’t want to draw any attention to themselves by celebrating it.

Annointed Morning (Life) – While not an official holiday, the Hall of Records keeps a formal census of children born in Sigil before peak on Life. Having Life as one’s name day is considered especially lucky, and is a good way of making oneself stand out from the crowd. A non-faction-affiliated group called the Annointed Sisterhood congregates just after peak to announce all the births, and each family on the list receives a small gift of freshly baked bread.

Efreeti’s Court (Fire 1) – All of Ethil Rué, the Bazaar fills with exotic visitors from the Inner Planes, selling all manner of strange wares. Fire 1, however, marks the official arrival of a huge trade caravan from the City of Brass. Sale of slaves is forbidden inside Sigil, but just about everything else that can be sampled from that vast Inner Planes marketplace abounds on this day. Chant is that no small amount of souls gets whisked off to the Plane of Fire, caught up in the swirl of excitement each cycle, never to be seen again.

Ordial Day (Astral Day durin Ethil Rué) – There isn’t always an Astral Day during Ethil Rué, but those cycles where there is, a few of the more creative factions come together to celebrate the mysterious, un-visitable Ordial Plane. This theoretical place is said to connect the Outer and Inner Planes, but has never been observed by anyone who came back to tell about it. Ordial Day is a favorite day to spread conspiracy theories and play pranks.

Para Festivals (Astral Days that fall between two Elemental Days) – More rare than Ordial Day are the Para Festivals, which only occur in cycles where an Astral Day lands between two Elemental Days. Depending on which elements are observed, the Sensates put together a whole day of festivities related to the appropriate Para-Elemental Plane. An Astral Day between Fire and Air results in a Festival of Smoke, where every exotic leaf and weed in the multiverse is collected, rolled, and puffed on. Air and Water result in the Festival of Ice, where Sensate wizards turn the roads to ice and engage in sled races and epic snowball fights. Water and Earth cause the Festival of Ooze, which results in quite a lot of naked mud wrestling. Earth and Fire bring the Festival of Magma, the hardest to celebrate by far, which almost always ends with property damage and a few poor sods sorched to death.

Dead-Book Festival (Death) – The Dustmen don’t much care they only get one day a cycle where the other factions get a whole month. They care so little, in fact, they don’t even sponsor an event on their one day. Instead, the Sensates throw a one-day parade throughout the streets adjoining the Civic Festhall celebrating all the facets of death. Folks dress up like skeletons and other undead creatures, share legends and stories of the various powers related to death, and essentially make mock of everything the Dustmen stand for.

Doomguard Riots (Fire 2 – Air 2) – The Elemental Days of Ethil Rué Rufaan are particularly nasty for folks minding their own business in the Lady’s Ward. The Sinkers sponsor a massive faction-only melee outside the Armory (the second most popular gambling event of the cycle), offering every upstart in the faction a chance to prove their martial prowess. That’d be bad enough, but the more unseemly members of the faction always use the melee as an excuse to cause general mayhem throughout the Lady’s and Lower Wards. Used to be the Doomguard would keep a lid on the violence, but since the newest factol took over that hasn’t been a priority. There’s always a body count by the end of the week.

Day-Again of Foul Luck (any Astral Day that follows or precedes a like-numbered day of any month) – Day-Again usually only comes once a year, and always at a different time. Whenever two days in a row have the same number — say, the eleventh of Arcanuus immediately followed by the cycle’s eleventh Astral Day — everyone spends the day looking over their shoulder for the especially bad luck following them around. Chant is that any misfortune that comes your way on the first day is sure to happen a second time on Day-Again, and any good fortune you enjoy on the first day is a cert to be undone.

Tax Holiday (Arcanuus 18) – Of course the one and only holiday sponsored by the Fated would be about collecting taxes. While its name implies it’s a holiday from paying taxes, Tax Holiday is quite the opposite: all fees, fines, leins, bonds and overdue payments come due on this day, and the faction offers its members a cut on anything they manage to collect. Lots of doors get knocked in on Tax Holiday, and lots of berks get thumped by the Hardheads for inability to pay.

Festival of the Arts (Marlithuus 1-7) – The first week of Marlithuus was seized upon by the Sensates as a celebration of the creative energies inherent in the tides of chaos. Everything from orchestras to puppet shows are lauded in the Festhall during the week, and special consideration is given to pieces that are unique, rather than those which display actual quality.

Festival of Blood (Marlithuus 6) – Sponsored by no one in particular, but practiced nonetheless by no small number of chaotic fiends, the Festival of Blood celebrates all the monstrosities of the Blood War smack dab in the middle of the Festival of Arts. While some high-ups have taken to having mock-parties “celebrating” the Festival of Blood behind the secure walls of their manors in the Lady’s Ward, the Festival proper always leaves a gruesome wake in the Hive. A popular Sigilian joke is that the Festival of Blood is the only holiday the Lady in Pain celebrates herself, as it usually sees a few of the more malicious participants flushed down into the Mazes.

Weeping Day (Marlithuus 33) – Against all odds, one splinter group of Bleakers have actually embraced their official space in Sigil’s calendar with Weeping Day, a day to lament the grotesqueries of mortal existence. Though there is no formal planning, most everyone in Sigil manages to get an earful about poverty, or the high murder rate, or unfair application of law, or this or that injustice at some point during the day. Truly canny alehouse proprietors will capitalize on the day by offering discount swill.

Forum of Chaos (Graalember 1) – Similar to the Forum of Law and Order — and also paid for by the Guvners, Harmonium and Mercykillers — on the day of the Forum of Chaos only members of the Xaositects, Doomguard and Bleak Cabal have the floor. Most see the sponsorship as a cynical PR move; the lawful factions get to claim moral high ground over their enemies by making a cursory attempt to let them have their say. Turnout is generally mixed, and some cycles the Hall of Speakers sits empty all day. Other cycles the Hall is filled with swirling, beautiful nonsense. Many Sigilians fondly remember the year 106 Chaosmen all lined up and each delivered the exact same 8-minute speech about the abhorrent state of rodent meat available in the Hive.

Ysgardian Revelry (first full week with an Astral Day in Graalember) – The plane of Ysgard is no slouch when it comes to drink and debauchery, but the plane has no official recognition in Sigil’s calendar. That didn’t stop a few Ysgardian powers from organizing its denizens to come to Sigil and throw a week-long party, though. To many Sigilians, the Ysgardian Revelry begins a two-month-long holiday season, with the planes of Ysgard and Arborea competing with endless supplies of food and drink. The Ysgardian Revelry tends to be a bit more violent than the Hardheads would like, and a few of them get thumped each cycle when trying to break things up.

Tourney of Chaos (Graalember 11-15) – The Godsmen sponsor various shows and competitions for craftsmanship every year, but the biggest annual event is the Tourney of Chaos, in which a portal to Limbo is opened and entrants from both sides of the door demonstrate their skill with chaos shaping. Githzerai allies on the Limbo side guarantee safety from the dangers of the plane, so the people of Sigil get to see strange and wonderful things from literally beyond their imagination.

Day of Zerthinon (Graalember 31) – A somber day of reflection for the githzerai citizens of Sigil, to remember their liberation from their illithid captors and to contemplate their hated foes, the githyanki. The day means something a little different for each individual githzerai, but informal gatherings tend to pop up all over Sigil, some of which are observed with curiosity by those on the outside.

Bariaurmat (Graalember 38 – Ghaela 1) – This two-day celebration seems to exist only because the bariaur want it to. While most folks can’t participate in the many frequent bouts of head-butting, the vast quantities of drink that spill in from Ysgard and the Outlands during this time is more than welcome. One favorite activity of Bariaurmat is for a bariaur to make a public wager with some humanoid berk, who climbs aboard the bariaur’s back and tries to stay on while the bariaur kicks and thrashes about. Other cutters bet on what sort of injuries are sustained, instaed.

Grand Arborean Festival (Ghaela 1-7) – To many Sigilians, and certainly all Sensates, this is THE Festival of the year. When folks ask each other what they’re doing for Festival, or Fest, they’re inevitably talking about this weeklong celebration of all the finest, most indulgent food, drink, song and sex to come from the plane of Arborea. Especially hedonistic cutters have been known to bankrupt themselves during Fest, all trying to one-up each other in the quest to throw the most memorable feast imaginable.

Celebration of Dead Gods (last Astral Day of the cycle) – The only formal event sponsored by the Athar, this celebration is little more than a faction recruitment drive. Athar greybeards take careful notes throughout the cycle of powers whose grasp on their worshippers is slipping, realms that are shrinking, or clerics and paladins whose power is waning. Cycles where a new godly corpse winds up in the Astral are especially desireable. Most non-Athar participants are those berks who are just looking for any excuse to stretch out the Arborean Festival as long as possible.

Dabusdan (last day of the cycle) – The Dabus day of rest. Most Sigilians note it with trepidation, as the city’s silent caretakers are in very short supply. Depending on one’s faction and belief structure, it’s either a day to take the betterment of Sigil upon oneself, or a day to wreak havoc on the city’s infrastructure without those creepy dabus spoiling your fun. Rumor has it that nobody has ever been flayed or mazed by the Lady herself on this day, and none can recall seeing her form float about the city, either. Some really reckless berks use the day as an excuse to thumb their nose at the Lady’s laws. The Mercykillers are on sharp lookout for such foolishness.

In the run-up to my most anticipated game release in years, I thought I’d take a look back at some previous Metal Gear Solid games in the most arbitrary way I know how: tedious list-based fanwank! Each day until The Phantom Pain is in my sweaty, shaking hand I’ll be taking a look at one aspect of what makes the MGS series special and rating each game from best to worst. (Or worst to best, depending on your perspective!)

—

Good ol’ Ocelot. He’s everybody’s favorite gun-spinning, double-crossing, apple-crushing, torture-obsessed, moustache-sporting, trenchcoat-wearing supervillain(?).

Metal Gear Solid has lots and lots of characters, and while most are integral to the contained plot of whichever games they appear in, Ocelot is one of the few that has broad importance to the saga as a whole. While it’s hard to keep tabs on his plots and allegiances from story to story, it hardly matters when he’s chewing on the scenery.

Here are some of my favorite Ocelot moments!

—

#6: No Ocelot! Waaaahh!!

No one character appears in every single Metal Gear Solid game, but Ocelot comes close; Peace Walker is the only game he doesn’t grace with his presence. If Peace Walker has a bright and glaring failing, surely this is it!

I suppose it could be argued that this is an essential slice of Big Boss’s life story, free from hyper-manipulative agents such as Ocelot. And from a narrative perspective, I will grudgingly concede that three or four more layers of backstabbery wouldn’t have improved anything.

But in his absense there was nobody to spin guns or crack wise. Big Boss just completes his mission without anybody taking the piss. What a shame.

—

#5: Taking the Tanker

There’s not a lot of context for Ocelot’s actions throughout Metal Gear Solid 2. At first he’s working with Gurlukovich, but then he shoots Gurlukovich. Later he needs the President alive, so he shoots the President. He needs Olga and Solidus and Fortune to help take the Big Shell, so of course he shoots all of them too. At times it really feels like he’s betraying people for the sheer thrill of it. And also he’s possessed by a magic talking arm…? Weird. It all reeks of setup for a sequel, which I suppose was his primary role in Metal Gear Solid as well.

He makes a hell of an entrance, though. First, he emerges from the shadows at the end of the Marine commandant’s speech, complete with deprecating, sarcastic applause. Then he shoots everybody important, acts all smug about it, and proceeds to blow up the tanker you’ve spent the past two hours carefully sneaking around. And while most MGS villains wait until the final act to hop inside of a Metal Gear and start lipping off, Ocelot decides to break tradition and do it right at the beginning. All that’s missing is a bout of maniacal cackling.

Sure, there’s that stupid bit where Liquid Snake’s dead arm is taking over his brain, or whatever. But I choose to believe, within the context of MGS2, that Ocelot is just letting Liquid think that’s what’s happening.

—

#4: Betraying Colonel Volgin

Metal Gear Solid 3 is chock full of fantastic Ocelot moments. Set during the Cold War, we are treated to a much younger, much cheekier Ocelot. In that simpler time Ocelot still had all the bravado and aplomb he’s so well-known for, but hasn’t yet tempered it with experience. As a result, quite a lot of MGS3 shows Ocelot taking his lumps, not from magically-appearing ninjas or supernatural talking hands, but simply the result of his own lack of humility.

There’s always the question of just who’s side he’s on, though. Very early on Ocelot develops a rivalry with Naked Snake that transcends his orders as a Soviet officer or an American CIA double-agent. While most of the rest of the characters seem to be disciples of The Boss, Ocelot becomes infatuated with Snake instead. As a result we’re treated to a lot of great character moments where Ocelot, dangerous though he is, just so very desperately wants senpai to notice him.

My favorite scene, though, is Snake’s confrontation against the dispicable Colonel Volgin. When Volgin orders Ocelot to stand down, depriving him of the showdown he feels he deserves, you actually feel for the little bugger. Ocelot responds to the situation by abandoning all pretense of being Volgin’s subordinate and openly starts rooting for Snake to win, going so far as to throw his equipment to him and giving him some encouraging finger guns.

The moment when Volgin shouts in exasperation, “Just who’s side are you on!?” is the moment Ocelot becomes the man he’s destined to be.

—

#3: The Torture Event

Leave it to Metal Gear Solid to make a rote button-mashing minigame engaging and memorable. The rules are simple: Snake’s life bar will constantly drain as Ocelot electrocutes him, and you can mash the button to make the bar goes back up. If you die, the game doesn’t let you continue. If you’re about to die, and you don’t want to replay the last hour of backtracking, you can hit another button to give in to the pain… but then you get the bad ending.

We know the rules so clearly because Ocelot explains them to us, as though it were a game. Which it is, I suppose, to the guy holding the PlayStation controller… but it doesn’t feel that way. While Snake is strapped half-naked to a metal table waiting for the shocks to start, Ocelot spells the situation out in terms that we-the-player understand all too clearly. He taunts us if we haven’t saved recently. Admonishes us for thinking about using a turbo controller. Calls us back to his torture dungeon, over and over, if we can’t figure out how to escape his prison cell.

By the fourth session, when your forearm aches and your hand is cramped up from all the mashing, Ocelot’s offer of making the pain end start ringing all the more true. The way he gets into your head with a combination of total moral depravity and gleeful fourth-wall breaking… it’s no wonder this horrorshow is Ocelot’s most famous scene in the series.

—

#2: Final Fist Fight

Throughout Metal Gear Solid 4 Ocelot (properly Liquid Ocelot, at this point) remains a step or six ahead of the player at all times. And yet, it still feels like a cheat, because there’s that nagging sense that Ocelot did all the work and got all the character development, only for Liquid to take over his brain at the tale’s end and take all the credit.

Ocelot doesn’t get to take control of SOP by setting off fireworks on the Volta. Ocelot doesn’t get to face off in an epic Metal Gear vs. Metal Gear battle at the docks of Shadow Moses. As great as these scenes are, it keeps coming back to that stupid talking arm from MGS2, and the knowledge that Liquid is stealing the spotlight. If Liquid was going to be the big bad in the end anyway, what was the point of that great after-credits monologue from MGS1?

But then we get to the final battle, not only of MGS4, but of the entire Metal Gear saga. No nanomachines, no weapons, no equipment; just two old men pummeling each other senseless, mano-a-mano. After a few punches, Liquid’s MGS1 character model flashes on the screen, and the name beneath his life bar changes from “Liquid” to “Liquid Ocelot”. A few punches later, the flash displays the talking arm scene from MGS2, and his name switches to simply “Ocelot”. What’s more, Snake’s name changes too — to “Naked Snake”.

Then the realization of what’s happening finally hits home: there never was any Liquid. Ocelot is such a chessmaster that he had to fool himself in order to complete his schemes. The player controls Snake in this fight, but we’re seeing things from Ocelot’s perspective. As Snake clobbers him, he regresses back through the damage done to his psyche over the years until, in his own mind, he’s a kid again, the world around him fades entirely away, and he gets his long-awaited tussel with Big Boss.

It’s a fine and fitting end for the character, but it’s cathartic for the player as well. After many years of cursing the stupid talking arm subplot foisted upon us by MGS2, we get to finish off the series with a real fight against Ocelot where we literally beat the Liquid out of him.

—

#1: Guess we’ll wait and see…

Ever since his first appearance in the Phantom Pain trailers, I’ve been giddy with anticipation to see what sorts of shenanigans Ocelot gets up to during his time working with Big Boss. This time around he won’t be a villain. Or, at leat, he won’t be an antagonist. It’s a new role for the character, and I’m more excited to see how it plays out than I am about any other part of the story.

Of course, it may all be a ruse, and there’s another heel-turn waiting in the wings to catch me off guard. If that’s the case, though, I don’t think I’d have it any other way. Godspeed, you marvelous bastard.

—

That brings us to the end of Metal Gear Memory Lane, but I have one more little surprise for you tomorrow, just as The Phantom Pain hits our PlayBoxes and X-Stations. Thanks for taking the journey with me!

In the run-up to my most anticipated game release in years, I thought I’d take a look back at some previous Metal Gear Solid games in the most arbitrary way I know how: tedious list-based fanwank! Each day until The Phantom Pain is in my sweaty, shaking hand I’ll be taking a look at one aspect of what makes the MGS series special and rating each game from best to worst. (Or worst to best, depending on your perspective!)

—

The worlds of the various Metal Gear Solid games are very finely detailed. My first exposure to the series was Metal Gear Solid 2, and I recall my mind being blown while watching my friend pick individual bottles of ketchup and mayo off of a pantry shelf with his gun. A few years later I spent a week or so frustratingly plugging away at Metal Gear Solid 3, trying to figure out how the goddamn game wanted me to play it without a radar. Turns out the answer was quite simple: it wanted me to stop worrying so much, and find my own solutions for each map.

As many bullet points as each game’s feature list has, though, excessive replays will leave you with the feeling that there’s a little something still missing from the equation. Here are a few little extras I really wish each game would have included.

—

#6: Backup on Codec

The gaggle of support characters Snake can ring up on his radio or codec was a huge part of the first three Metal Gear Solid games, and even the 8-bit Metal Gear 2 before that. They provided helpful hints and suggestions about gameplay elements when the player was stuck. They carried a lot of the weight of fleshing out the game worlds with backstory and character development. Sometimes they meta-gamed you, as in one especially memorable case in MGS1 that forced the player to, literally, think outside the box.

But in Metal Gear Solid 4, Otacon and Rose is all you get. Which isn’t to say anything against these two characters; Otacon has always been a personal favorite, and Rose is actually quite pleasant to talk to without the whole nattering girlfriend undercurrent. But two contacts? In the MGS game with the most gameplay features, the biggest cast and the most bloated plot?

There’s a wealth of options we’re missing out on here. We can’t call Campbell to get mission updates. We can’t call Meryl or Raiden to get detailed info about the environment and conflicts we’re sneaking through. We can’t call Drebin to hear how big his boner is over the semi-automatic recoilless carbine we just picked up. We can’t call Sunny to hear about all the fantastic Konami games she’s playing on her PlayStation Portable™.

As a result, a big part of the essential MGS experience is lost, and MGS4 is the poorer for it.

—

#5: Pause During Menus

The action in the first four Metal Gear Solid games paused while you went into your equipment menus, allowing you a few precious moments to think about the best load-out to clean up whatever problem you just caused for yourself by rolling into that patrolling terrorist’s line of sight. This was necessary because, as big a deal as Snake’s commanding officer makes about going in light, within ten minutes he ends up with an entire garage of weapons and gadgets strapped to his back.

Peace Walker is a multiplayer game, though, and it wouldn’t do for Player 1 to pause Player 2’s action because he’s swapping out his stun rod for his stun grenades. So in that game, instead of pausing the action, the menu screens only pause Snake. While you’re standing there rifling through your, er, rifles, all of the enemy soldiers still have their full range of movement. This has been the cause of more than one frustrating death.

A necessary evil in the world of multiplayer, to be sure, but Peace Walker applies this same limitation even if you’re playing by yourself. The feature isn’t used to create a more realistic or immersive experience, like it is in Ground Zeroes. In that game Snake can only carry a couple of items, and has a clear visual indication of what he’s doing in the game world while the player is dottering around the menu. In Peace Walker the player is carrying around a boatload of stuff, and Snake just stands stock still and upright while his player makes up his mind.

It’s usually not too much trouble to duck around a corner or into a shadow to get your equipment sorted… but the game gains nothing by forcing this restriction.

—

#4: Start with the HF Blade

Every Metal Gear Sold player who wanted Grey Fox’s sword had their prayers answered at the end of Metal Gear Solid 2 when Snake presents Raiden with the High-Frequency Blade. Suddenly the player had much cooler melee options than punching or grabbing, and a use for that second control stick which mostly just sat there unloved throughout the game. The HF Blade had a very satisfying motion to it, giving Raiden new avenues of offense and defense to explore: he could use it to deflect bullets, he could do wide sweeps or quick stabs, and if he was feeling really fancy he could execute a Zelda-style circle slash. It gave definition to a character who, by design, had spent the whole game without an identify of his own. It felt like the kind of thing the whole game could have been based around.

Unfortunately, all those players who had their prayers answered had them rudely dashed again when the HF Blade was taken away from them after two scenes and a boss fight. But there was hope: it’s MGS tradition to offer new toys to play with on replays. Snake even mentions his magic bandana in the very scene he gifts Raiden his sword! Maybe the HF Blade will be in Raiden’s inventory next time we play, letting us slash our way through screens we had to carefully sneak through previously?

It was not to be. Though Raiden would get his due as Official Ninja Badass in a spin-off game over a decade later, the sword in MGS2 is forever relegated to being an endgame gimmick. This is a pretty serious grievance in a universe where Old Snake can start his mission with voodoo dolls and a solar-powered death laser.

—

#3: A Way to Skip the Backtracking

Twice during the course of his infiltration of Shadow Moses, Snake has to drop what he’s doing and backtrack to old areas for pretty silly reasons. First he has to abandon his bleeding comrade and return to an area at the very start of the game to find a sniper rifle. Later, he has to criss-cross a screen full of boring, empty catwalks in order to reach old areas so his magic key changes shape. I see what they were going for here. In the first case they needed an excuse to get Snake away from the area so the bad guys could kidnap his girlfriend. In the second, they had sixteen barrels of exposition and needed a way to pace it out over a few extra screen transitions.

On replays, though, all the backtracking accomplishes is forcing me to be very, very bored for a very, very long time right at the tail end of my playthrough.

The Gamecube remake of MGS1, The Twin Snakes, solves both of these problems in really handy ways. There’s still a sniper rifle way back in the armory, if you want one, but there’s a non-lethal rifle in a much closer room, for your convenience. And as for the cardkey, there are handy pipes of liquid nitrogen and hot steam right there in the hangar ready to fulfill all of your magic key needs.

It’s considered an MGS faux pas to say anything positive about The Twin Snakes, though, so for purposes of this article I’m forced to ignore it. Too bad, because otherwise I’d be inclined to give MGS1 perfect marks in this category.

—

#2: Camo Quick-Change

A big element of Metal Gear Solid 3 was surviving in a harsh, natural environment. In addition to his equipment load-out Snake had to worry about finding food, tending to injuries, mapping his surroundings, and using camouflage. There wasn’t an elegant way to handle all these new features in the standard L2/R2 menus, though, so for the first time an MGS game got a big, obtrusive subscreen to handle it all. The game called this the “Survival Viewer”, but we all knew it was really a “Pause Menu”, and mostly just tolerated it.

For an even mildly-skilled player, all the contents of the Survival Viewer were pretty easy to ignore. There’s tons of food littered around the game world, injuries are few and far between as long as you’re half-decent at stealth, and no single area is really large or confusing enough to require a map. Camo, though, remains important throughout the game, and it gets really obnoxious going into the menu every few minutes so Snake can play dress-up.

The end result: there are a few different strategies for using camo in MGS3, and none of them are close to the probably-intended “pick the best camo for the situation you’re in”. Some players only switch camo when the environment changes drastically. Others ignore the system entirely and rely on distance and line-of-sight shenanigans to remain unspotted. And others put on the tuxedo and zombie face paint and play the entire game like a karate conga line.

Point is, the ability to hot-swap between the two or three most useful camo options would have gone a long way to making the mechanic feel useful, rather than vestigial.

—

#1: A Boss Fight

Steam says I have 120 hours played in Ground Zeroes. That can’t be right. A counter must have glitched out somewhere, or maybe I accidentally left the game running in the background for a couple days. Or, well, maybe I really have sunk that much time into the game. For as little content as Ground Zeroes has, there’s a tantalizingly huge combination of ways each of the missions can be solved, and lord knows I’ve put in the time to explore them all. I shudder to think what my playtime is going to look like after a year of The Phantom Pain.

For all the fun to be had, though, Ground Zeroes is missing what is, for me, one of the defining elements of the MGS series: a boss fight. For a demo that is supposed to show the breadth of what the Fox Engine is capable of, that’s a pretty huge and glaring omission.

Maybe, with the incredible amount of freedom afforded to the player, there just isn’t room in the MGS5 games for a more narrowly-structured one-on-one combat experience? If that’s the case, it’s incredibly saddening. But if it’s not — and I have faith that it’s not — why not put a little taste of that in the prologue?

The main mission, Ground Zeroes itself, isn’t the place for a boss fight. It’s pure infiltration and extraction, and stopping things partway to force a gimmick fight would have felt very weird. But the two Extra Ops missions are non-canonical sillyfests, and would have been just perfect. Instead they tease a Psycho Mantis rematch which never materializes, and makes Raiden fire rockets at helicopters for ten minutes.

—

Alright, that’s enough bitching. Tomorrow, we’ll take a look at my favorite character from the MGS saga, relive some of his most memorable moments, and look forward to his triumphant return in The Phantom Pain. Thanks for reading.

In the run-up to my most anticipated game release in years, I thought I’d take a look back at some previous Metal Gear Solid games in the most arbitrary way I know how: tedious list-based fanwank! Each day until The Phantom Pain is in my sweaty, shaking hand I’ll be taking a look at one aspect of what makes the MGS series special and rating each game from best to worst. (Or worst to best, depending on your perspective!)

—

Metal Gear Solid games always have large casts of colorful characters. You have the player character, his radio support, a squad of elite soldiers for boss fights, a scientist or two what needs rescuing, an NPC helper buddy who usually needs babysitting, a character or two of ambiguous allegiance with mysterious hidden agendas, the big bad, the real big bad behind who you thought was the big bad, a shadowy figure from the US government who is only mentioned in passing, and then a sprinkling of cameos and references to characters elsewhere in the series.

With such a huge population of folks and only so much spotlight to go around, you’d think there’d be no room for characters who don’t pull their weight in the story. You’d think that. Alas, you’d be wrong.

—

#6: Johnny

Strictly speaking, Johnny isn’t a new character. In the first two Metal Gear Solid games he’s a generic soldier with unforunate stomach problems who has bad luck with the ladies, and in Metal Gear Solid 3 he’s that guy’s grandfather. As a fun little easter egg, the character is fine. He offers a sorely-needed humanizing element to the generic soldiers Snake spends so much time teabagging and/or shoving into lockers. We all wanted him back in Metal Gear Solid 4, but… just not like this.

We first meet Johnny as part of Rat Patrol 01, Meryl Silverburgh’s PMC oversight unit. This already stretches disbelief rather thin. I’ll buy one of the Shadow Moses terrorists falling in with the Gurlukovich mercenaries, considering the tenuous connection through Ocelot and the fact that he’s presented as a silly offscreen cameo in MGS2. But Meryl’s group is an official arm of the US military. Didn’t anyone do a background check? Doesn’t Meryl recognize him?

Anyway, the character is played for laughs for a couple of acts, which I originally took as just another example of MGS4 overdoing itself a bit. But no, in the final act it turns out we’re supposed to take the character totally seriously, as he’s one of the three soldiers hand-picked to be launched into the heart of Liquid’s base. Even more ridiculous, we discover that Meryl takes him seriously, and I honestly thought she had more sense than that.

Don’t get me wrong, combining a massive violent shootout with a romantic marriage proposal between a woman who insists she has no interest in men and a dude whose only defining trait for ten years has been “he poops himself” is hilarious and wonderful. But it’s such a stark, comedic contrast to the overly-serious tone of the rest of the endgame that all I can do is roll my eyes at it.

—

#5: Major Raikov

Lots of MGS fans spent the years between Metal Gear Solid 2 and Metal Gear Solid 3 hating Raiden, the anime prettyboy who replaced Solid Snake as the player character. So when MGS3 begins and Naked Snake has a Raiden mask in his inventory, everyone just thought it was one of Kojima’s little meta-pokes at his own canon. If that’s all it had been, we could have just chuckled at it and gone on with our lives, but no. It turns out there happens to be an enemy officer who looks exactly like Raiden, and you just happen to have your face in his inventory, and using said mask to disguise yourself as said officer is an actual gameplay objective.

Well, okay, now that there’s a lampshade on it we have to stand up and take note. Is there an in-universe reason why this Russian officer just happens to look exactly like an albino Liberian assassin who won’t be born for another twenty years? Did the Russians have their own version of Les Enfants Terribles ten years before the Americans thought of it? Who decided an American CIA agent needed a mask of this officer on what was supposed to be a two-hour extraction mission?

There’s a lot of fun stuff you can do with the Raikov disguise, once you have it. But man, the game has to do some pretty crazy gymnastics to justify what otherwise is just a quick visual gag. I’ll admit it’s ultimately worth it, though, to hear The Boss call Raiden a fairy.

—

#4: “Mr. X”

Metal Gear 2 has a mysterious character that rings you up to tell you where mines and invisible lasers are hidden who turns out to be Grey Fox. So, of course, Metal Gear Solid also has a mysterious character that rings you up to tell you where mines and invisible lasers are hidden who turns out to be Grey Fox. And since MGS2 was written as a subversive version of MGS1 it, too, has a mysterious character that rings you up to tell you where mines and invisible lasers are hidden, only this time it doesn’t turn out to be Grey Fox. Whoa!

This time, the player’s shadowy benefactor turns out to be Olga Gurlukovich, the leader of the Russian mercenary group patrolling the Big Shell. And I’m certainly not arguing that Olga is at all unnecessary, or that her agenda of secretly helping Raiden from behind the scenes is a worthless plot element. Just the contrary! Olga’s plot is one of the high points of the series, and her reasons for aiding Raiden ring particularly true amongst a cast where everyone is backstabbing everyone else.

What I don’t get, though, is why she needed to literally dress like Grey Fox to accomplish her role in the story. Yes, the Patriots were attempting to re-create Shadow Moses as closely as possible, but that didn’t translate literally in most other parts of the exercise, so why just this one thing? The real reason is because Kojima wanted us to have a “wait, Grey Fox is back!?” moment, and a scene where Ocelot almost loses his arm again, and a reason for Raiden to use a sword in the final act. But it still feels flimsy, and cheapens the role of an otherwise great character.

—

#3: Nastasha Romanenko

In a game about the evils and dangers of nuclear weapons, Nastasha Romanenko’s job is to repeatedly inform Snake about the evils and dangers of nuclear weapons. Campbell initially informs Snake that Nastasha can provide him information on the weapons and hardware he comes across in his mission, but nine times out of ten she instead serves up dire and possibly dubious factoids about nuclear stockpiles around the globe. These conversations are never useful in the context of Snake’s exploits in Shadow Moses. In fact, it’s entirely possible to complete Metal Gear Solid without ever adding her to your codec screen.

Nastasha does serve a quasi-important role in the plot, at least inadvertantly. Much of the back half of the story involves a game of Spot the Spy, where Snake has reason to suspect there’s a spy amongst his support team. In that sense Nastasha is a bit of a red herring, a warm body in Snake’s phone book for the real traitor to hide behind. Maybe some players spent a good portion of the game suspecting her…?

Still, it’s a pretty flimsy justification. Nastasha herself is so unimportant that she’s the only living character from the first two MGS games not to come back for Metal Gear Solid 4. Heck, even a few of the dead ones miraculously made an apperance!

—

#2: Cécile

In Peace Walker, Snake doesn’t have a support team, per se. Instead, characters will chime in on the radio at various points in the mission to offer advice or encouragement. Cassette tapes that unlock between missions offer a bit of background and development, but Cécile’s tapes come across like… well, like a birdwatcher with a bad French accent taking up space in a Cold War story.

As far as I can tell, Cécile serves three minor purposes in the plot of Peace Walker: 1) to mimic bird calls for one mission where Snake has to identify the song of a particular jungle bird, 2) to dwell a little too much on how Dr. Strangelove likes the ladies, and 3) to provide a “girl time” entry in Paz’s diary. Other than that, it seems incredibly forced that a birdwatcher from Paris would want to hang out with a scruffy military organization after escaping with her life from a mad scientist.

Actually, there is one more thing. In one really bizarre conversation, Kaz Miller points out that Cécile’s full name sounds a bit like “Kojima is God” in Japanese. That’s probably just a coincidence. After all, just how self-absorbed would you have to be to invent a character for the sole purpose of a juvenile power trip?

—

#1: Hideo Kojima

OH COME ON.

—

I probably have to come clean at this point: I really am a huge fan of the MGS games. I tease them because I love them, but also because as great as the games are, they’re far from perfect. It’s just more fun to complain than to praise. Tomorrow, let’s complain about some features missing from these otherwise highly detailed and feature-rich games! Thanks for reading.

In the run-up to my most anticipated game release in years, I thought I’d take a look back at some previous Metal Gear Solid games in the most arbitrary way I know how: tedious list-based fanwank! Each day until The Phantom Pain is in my sweaty, shaking hand I’ll be taking a look at one aspect of what makes the MGS series special and rating each game from best to worst. (Or worst to best, depending on your perspective!)

—

Innovative gameplay ideas are one of the mainstays of the Metal Gear Solid series. When detractors poo-poo Kojima’s narrative style by saying he just wants to make movies, it’s pretty easy to shut them down by pointing to any number of creative gameplay sequences such as Psycho Mantis or The Sorrow. Or by pointing to game mechanics which open up opportunities for interactive storytelling, like stamina bars or the Metal Gear Mk. 2.

When you pitch enough things at the wall, though, a few of them aren’t going to stick. Each game has a few stinkers that I dread just about every time I replay the games. These are their stories.

—

#6: Intel Operative Rescue

Including the Side Ops from Ground Zeroes in these lists does seem a bit disingenuous, but considering you can clear the main story mission in under ten minutes by adopting a fun-loving devil-may-care attitude to gunning down marines it’d be kind of slim pickings otherwise. In truth the Side Ops make up quite a lot of the game’s meat and potatoes, each offering slight twists on your mission objectives in the great big sandbox of Camp Omega. They’re a big part of the game, is my point, and dismissing them because they don’t “count” is short-sighted.

The Intel Operative Rescue mission, however, is a shining example of the worst gameplay the Fox Engine has to offer. Instead of being a variation on the scout-and-sneak gameplay of the main mission, it instead boils everything down to a linear rail shooter. A series tradition, to be sure, but a kind of bland and frustrating one. I don’t play these games so my guy can mow down everything in sight with infinite machinegun. I like for that option to be available as a way to mess around on replays, but it’s just not what Metal Gear Solid is good at.

I admit I’ve been biased against rail shooter segments in ever since the original game had me shoot through Liquid’s invincibility frames for five straight minutes. These segments simply aren’t engaging to me; they are the lowest possible form of action gameplay. That being said…

—

#5: Motorcycle Chase

…the rail shooter segments are very rarely the worst parts of the game. That I picked them as the worst example of bad gameplay from Ground Zeroes and Metal Gear Solid 3 speaks to the high quality of the rest of those two games.

The motorcycle chase scene at the end of MGS3 is a thrilling, adrenaline-pumping escape sequence… the first time you play the game. As early as the first replay you see the scene for what it really is: an incredibly long, barely interactive cinematic. It’s broken up by a short sniping segment and one of the most exciting boss fights in the series, sure, but once you have enough MGS3 experience it just becomes a chore you have to do to make the game let you win.

There is a silver lining, though: by equipping the Cold War camo you earn by stamina killing Colonel Volgin, the motorcycle soldiers won’t shoot at Snake as long as he’s facing them. Instead they just drive along saying “Damn it!” over and over. This turns the scene into a weird parody of itself, a kind of Scooby Doo chase. Once that stops being funny, it at least gives you a chance to put the controller down and take a bathroom break.

—

#4: Oil Fence Sniping

Sniping scenes in video games have to be done very, very well, if they’re going to work at all. Done well, they can be very tense and exciting, like the battle of wits against The End in Metal Gear Solid 3. Done badly, they turn into arduous experiences like the battle of suck against Crying Wolf in Metal Gear Solid 4. Somewhere in between is Metal Gear Solid 2‘s oil fence sequence, which is neither tense nor arduous. It’s just kind of… there.

Raiden’s NPC helper buddy moves automatically along a long, dangerous path with no cover. His job is to stay behind and clear her a path by taking out enemy soldiers, mines, and flying robot machineguns along her route. The solution is to put on the thermal goggles, pop some pentazamin and shoot anything that lights up bright white.

Resource management isn’t an issue, since the ammo box near Raiden’s position magically grows back every few seconds. Messing up is unlikely, since the targets are so obvious and your NPC helper has enough health to survive several encounters. Plus, Solid Snake is hanging out in another vantage point and will fire on anything you don’t, just in case you absolutely can’t be arsed.

The gameplay isn’t challenging or engaging, but it sure is long. There are a couple of neat easter eggs to discover along the way concerning Raiden’s silly hair and an enemy soldier who poops himself, but that’s about it. And in the end a vampire jumps out of the ocean and kills your NPC friend anyway, just to make sure you don’t even accomplish anything.

—

#3: The Infinite Staircase