I love the idea of multiclass characters in Dungeons & Dragons, but I hate how it’s usually implemented.

I’m a student of AD&D Second Edition, and the dual- and multi-class rules in that game were very strict. The idea was that a dual- or multi-classed character was a rare and powerful breed. It involved a major alteration to your character concept; a Fighter/Thief was meant to be played much differently than a Fighter or a Thief. In addition, not every class could be multi’d; a Paladin was a Paladin for life… unless he strayed from his path and became a Fighter.

Third edition changed the multiclass rules in such a way as to open up more character variety. Now any race could be any class, and what’s more, you could take as many class levels in however many classes you liked. The added character options were cool in theory, but they often led to silly decisions like “I’ll be a L10 Wizard/L1 Fighter, because I mostly want to be a Wizard but I want a few extra HPs and weapon proficiencies.” The addition of prestige classe and splatbook material made this even sillier, with bizarre “optimized” builds where a player might spread his EXPs across seven different classes.

As far as I can tell this practice of “dipping into” another class for a level or two in order to gain some mechanical bonus was retained and even encouraged in fourth edition. Gone was the idea that your character’s class represented his adventuring career path. Instead of being part of who your character was, class levels were treated like dots on character creation screen.

Fifth edition seems to be trying to curtail the practice of “dipping in” in two ways. First, it places hard restrictions on ability scores for multiclass characters. If you want to dip into Wizard to score a few free attack cantrips, you first have to build your Intelligence to 13. (Or plan ahead by putting a 13 into Int at character creation.) The justification for this is that your character’s first class level is the culmination of all his training and experience up to this point in his life, and that picking up a second class requires a sense of natural aptitude so as to be able to pick up the concepts of the new class quickly.

The second way it downplays the practice is the way each class gains its class features. Most classes don’t get all their core features together until L3, which is three levels you aren’t spending in your main class. Further, most classes don’t get ability score improvements until L4, so if you multiclass too early or too often your ability scores are going to be lagging behind. Thus, multiclassing makes sense for a player who has a unique character concept in mind, and not so much for someone who wants to justify a patchwork 4/3/2/1/1 build.

(A third thing it does is to offer lots of watered-down versions of class features as feats. So if you’re just looking to dip in for a specific feature, you’re usually better off taking the related feat and not missing out on a level in your main class.)

Upon reflecting on the rules, though, and reading some arguments both for and against the new multiclassing system, I’ve decided they still aren’t strict enough. A player who spreads class levels more than two ways, to my mind, is metagaming at an unacceptable level. At the point you’re deciding whether your Druid/Thief needs a level of Fighter to round things out, you have left the realm of character concept behind and are starting to fiddle too much with the numbers. In addition, some classes, as described in the Player’s Handbook, are just more difficult to multiclass into than others.

With that in mind, I’ve sketched together these rules for players who want to multiclass. The goal is this: a character’s second class should be a skillset used to augment and flesh out the character’s first. A character should not have three classes. As a result, it’s easier to pick up classes with features that can be reasonably learned and practiced, and more difficult for those with stronger thematic concerns.

In this article I’ve ordered the 5e classes by how difficult they are to multiclass into.

—

Tier One: Easy, but…

Warlock

As far as I’m concerned, the only requirement for becoming a Warlock is forming a pact with some supernatural creature. Such creatures are in are in no short supply. A player who expresses interest in multiclassing into Warlock would be shortly contacted by such a being. That being said, such entities are often manipulative or malevolent, or at the very least have ulterior motives for giving away a fraction of their power. A multiclassed Warlock may quickly find himself at odds with his patron, or be faced with difficult moral quandaries they otherwise would not have faced.

—

Tier Two: Easy

Fighter, Rogue, Wizard, Cleric

It was a happy accident that the four easiest classes ended up being the D&D staples! But it makes sense. These classes are comprised mostly of skills which can be learned and practiced. In the D&D world anyone can pick up a sword and become reasonably competent with it, or noodle around with some low-level arcane magic. And having picked up the basics, the remaining 19 class levels are really just about honing your skills.

Anyone looking to multiclass into Fighter, Rogue or Wizard would need to state their intention at the beginning of a session, and then spend a considerable amount of energy during that session working towards their stated goal. Suffice it to say, this could really only be done during a roleplay session and not during a dungeon hack. (Even during a roleplay session, they would likely have to ignore the main plot in favor of their training.) At the end of the session, if they’d been sufficiently diligent and pass a few checks, they get enough EXP to go up one level in the new class.

Clerics would work the same way, except they would be restricted to gods whose temples or followers the player can immediately access, and they would have to be sincere in their desire to follow that god. A multiclassed Cleric who works against his god’s interests would lose those class levels until he shaped up.

—

Tier Three: Difficult

Bard, Monk, Paladin

Like the core four, these classes represent characters with skill, knowledge and training that can theoretically be picked up by anyone. They aren’t quite as broadly defined as the core four, though; being a Bard or a Monk implies a certain kind of outlook on the world that not everyone possesses. Being a Paladin implies no such thing; it’s a flat-out demand. What’s more, music schools and monastaries are in shorter supply than with the core four, and differences in opinion between teacher and student could end up being major roadblocks.

Picking up one of these classes would involve finding an NPC of the class who is capable and eager to teach, and that there are no major personality conflicts between that NPC and his student. The player would then be required to touch base with his teacher in order to train up to L2 and L3, at which point they pick their archetype and can advance as normal.

I would probably also require the player to continue this training uninterrupted until that point. If your Fighter decides to train with a stoic knight to gain levels in Paladin, said knight is going to question your devotion if you say, “Thanks for the first class level! I’ll be back after I get my next ability score advancement from Fighter!” I wouldn’t revoke the new class levels, but I would probably rule that the player had effectively abandoned his training after a bit of dabbling, and not allow them to advance in their second class without a serious show of dedication.

—

Tier Four: Effectively Impossible

Barbarian, Druid, Paladin, Ranger

These classes represent not just skills and ideals, but entire lifestyles. The skills in these classes are not things you learn to do, but rather are manifestations of how your character grew up and how that shapes his view of the world. The Barbarian’s ability to channel his inner rage is not a thing that can be learned; nor is a Ranger’s connection to nature, or a Druid’s ability to wild shape.

That said, if the player really latches onto something that exists in the game world as inspiration, I may allow that player to abandon their old class in favor of one of these. You wouldn’t lose your old class levels, but you wouldn’t be able to advance them anymore after switching. This represents a profound shift in the character’s goals and priorities; the abandoning of the old life for the new.

The reason Paladin is in both of these categories is because I could really see it going either way. It depends a lot on what the Paladin’s oaths are and how the character approaches the transition.

—

Tier Five: Actually Impossible

Sorcerer

The Sorcerer really blurs the line between race and class. Whether or not you’re a Sorcerer is a function of your birth; you either have it or you don’t. A character with six levels of Wizard does not suddenly wake up and realize, oh yeah, turns out I had magic blood all along!

The flip side of that is, I could see treating the first level of Sorcerer as an offshoot of race or background. That is, a character who woke to sorcerous power early in life but decided (for whatever reason) to not persue it. As a result, this is probably the only time I would allow multiclassing right at character creation. A player could take one level of Sorcerer to start, then say, “…but he denied his magic heritage and trained as a Rogue instead.” That character would start the game as a L1/1 Sorcerer/Rogue, and wouldn’t gain any EXP the first session he’s played. Thereafter he always has the option to take more levels of Sorcerer as he decides to develop his powers.

—

I don’t think any of the players in my current campaign have designs on multiclassing anytime soon, but hopefully if that changes they don’t find these rules too restrictive. If they do I’ll… I dunno… feed them to a roc, or something.

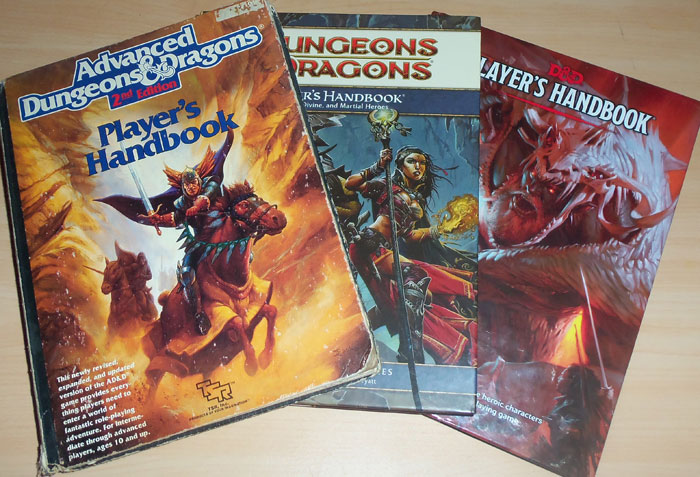

It would take pages and pages of text to share my thoughts on the new edition of Dungeons & Dragons. In short: I’m a fan. I love the books, I love the new systems, I love the new takes on old systems. I’m a gushing starry-eyed fanboy, despite what this old blog post about it would have you believe.

In case you don’t want to read what Old-Bitchy-Brickroad-From-2012 has to say, here’s the teal deer: Wizards of the Coast made some silly claim about how D&D 5e was going to appeal of fans to all previous versions, and I found that claim to be ludicrous. My feeling was that the history of D&D was too big a thing to condense into a single ruleset. All four editions (really six editions (but really nine or more)) of the game had dead ends and failed experiments which couldn’t be excised without losing something important. You had 2e with its motley of mechanics and dice systems (perfect for nerds who love fiddly numbers!). You had 3e with countless feats, skills, prestige classes and magic items (a min/maxer’s dream come true!). You had 4e with its tactical grid combat and ECL rules (everything a wargaming lootmonger could desire!). There was a lot of crossover between these wide and disparate systems, but I was of the opinion that they each had their niche. I was very skeptical of WotC’s “all things to all players” claim because I didn’t see how you could unify the things that various edition purists enjoyed under a single ruleset in a meaningful way. I figured the new edition would be a mishmash of redundant rules, vestigial mechanics and pages upon pages of optional minutia.

But 5e won me over! I could go on and on about how brilliant I think it is and how elegant some of WotC’s solutions wound up being. Indeed, if you’ve been watching my streams lately or showing up to our weekly gaming sessions, you’ve probably already had your fill of that. So instead, I’m going to narrow the focus a bit and talk about just one specific example of something 5e did very, very right: the Paladin.

—

A Quick Note About 3e

This document mostly references the Paladin class from second, fourth and fifth editions. There are two reasons for this. First, as we’ll see, I tend to define 2e and 4e at being at two different extremes of the tabletop spectrum, and 3e falls somewhere in the middle. So it’s somewhat less useful as a comparison to the new ruleset. And second, I don’t actually own a copy of the 3e rules, and in fact have never read them! I’ve played in many 3e games, but never run one, and I can’t remember anyone in our group playing a Paladin in one. I have vague ideas about their place and function in the game, but no firsthand knowledge and no reference material.

In other words, I’m sure there’s a lot to be said on this subject in regards to third edition. But I’m not the guy to say it. Sorry, 3e fans!

—

Second Edition Paladin

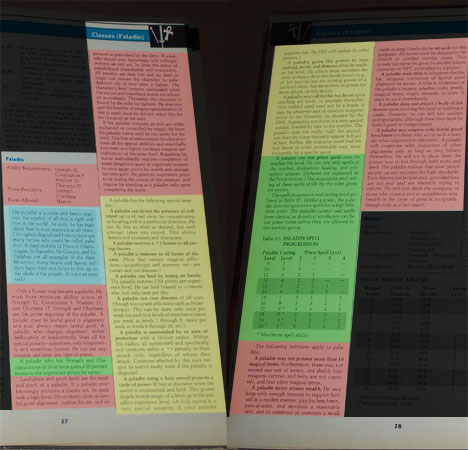

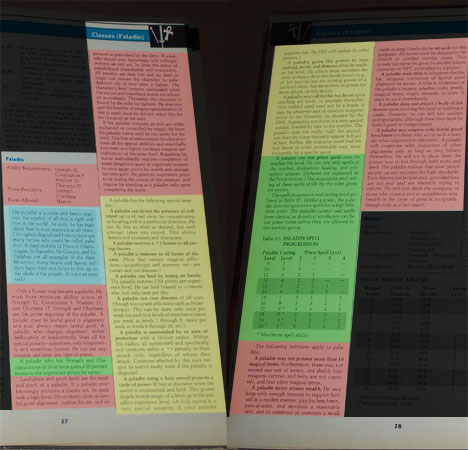

What you’re looking at is a badly-cropped photo of pages 27 and 28 of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition Player’s Handbook. It looks positively dinky compared to the class descriptions in later editions, but keep in mind that each of 2e classes were part of larger “class groups”. The Paladin shared some rules in common with the other two classes of the Warrior group, notably the Fighter. Most of the class description, as a result, can be summarized by “here’s how Paladins are better than Fighters, and here’s the price they pay for getting that way”.

And make no mistake, Paladins are better than Fighters. I don’t mean that in the sense that the game was poorly playtested or had terrible balance issues. I mean they were specifically designed that way. Nowadays it is considered a mortal sin to have huge power gaps between character classes, both in tabletop and video games. To do it on purpose would be unconscionable. But that’s how 2e is designed, honest injun! If we’re talking straight up game mechanics, there is no reason whatsoever* to play Fighter when Paladin is on the table

So to understand the 2e Paladin, we have to understand some reasons why it might not be on the table.

The answer lies in all the red blocks in the image above. Paladin is, by a very wide margin, the most heavily restricted class in 2e. It has the highest ability score requirement of any class and the narrowest range of race and alignment options. If you tell me you’re playing a Paladin in a 2e game, I already know 1) you’re a human, 2) you’re lawful good and 3) you managed to roll a 17 in a system where “4d6, drop the lowest” is a variant and not the standard.

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Much has been made about how Paladins must be lawful good, but even in 2e there is lawful good and there is lawful good. Paladins are expected to be absolute paragons of law and good, impeccable in word and deed. Lawful good is already a challenging alignment to roleplay properly, and Paladins in particular are at the very extreme end of that challenge. One slip-up towards evil and the Paladin loses all his class abilities, reverting to a Fighter of his experience level. This change is immediate and irrevokable, unless the Paladin acted under magical duress; in that case, he may have his class returned to him if he completes a dangerous quest of atonement.

On top of all that, the Paladin labors under some pretty severe loot restrictions. He cannot own more than ten magic items. He does not attract followers. He may keep only enough wealth to pay his debts; everything else goes to the church. He isn’t even allowed to bestow this wealth to the party. You’re reading all this correctly. Paladins are expected to ignore the primary reason for adventuring! He’s simply not allowed to partake in the standard kill/loot/kill/loot cycle most people play Dungeons & Dragons to enjoy!

In return for these huge restrictions, the Paladin enjoys many bonuses over the standard Fighter. Not the least of these are a straight bonus to all saving throws and innate protection from evil creatures. They have a class-specific magic weapon, the fabled holy avenger, whose might is as awesome as its name. And they get a warhorse buddy they can call to their side like that guy in Shadow of the Colossus. Oh, and healing, undead turning, and spellcasting abilities.

That may not sound like fair compensation for all the weight the Paladin has to carry. After all, every class in the game except the Fighter has cool features that make it unique, and they (mostly) get to keep their loot. So what does a Paladin player really get for picking such a difficult class? You’ve already guessed the answer: the class is its own reward. The roleplaying opportunities of the Paladin are endless. Simply having one around creates interesting conflict that often demands resolution outside of “kill all the orcs”. The Paladin often becomes the villain of the group as he seeks to hold the other members — even lawful good ones — to his impossible standards.

That’s why the Paladin isn’t balanced with the rest of the classes in 2e, and why it doesn’t need to be. It’s a class that demands far, far more of its player than “learn how to use your class abilities”. It’s not a class everyone is intended to play.

That sounds unfair and elitist to the ears of many modern gamers. Perhaps it is. But that’s where we start.

*No, weapon specialization is not why people play Fighters.

—

Fourth Edition Paladin

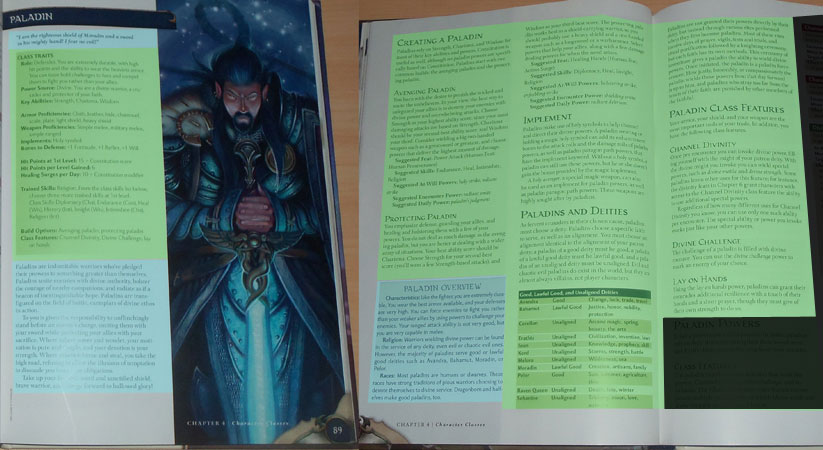

Here we have pages 89-91 of the Dungeons & Dragons Player’s Handbook: Arcane, Divine and Martial Heroes, or the 4e PHB. Allowing for the larger print in the 4e books, the actual description of the class is about the same length. Not pictured are the eight pages of individual Paladin class powers, twenty of which are “Something Smite”. Huge lists of powers are nothing special in 4e though; every class has those. The more notable difference is the lack of any restrictions or bonuses in 4e’s ruleset. The only limiting factor in playing a 4e Paladin is your desire to do so.

In fact, there are no rules at all regarding your Paladin’s behavior, save that his alignment must be the same as his deity’s. The Paladin is never in danger of losing any of his class abilities, regardless of how chaotic or evil he acts. From the PHB:

“Once initiated, the paladin is a paladin forevermore. How justly, honorably, or compassionately the paladin wields those powers from that day forward is up to him, and paladins who stray too far from the tenets of their faith are punished by other members of the faithful.”

This makes sense though, right? Unlike in 2e, there is no “base class” for a fallen Paladin to revert to. In 4e, Fighter is a unique class unto itself with powers all its own. It would be ridiculous to tell a 4e player, “Since you raped that orphanage, you lose all your Paladin powers. You’re a Fighter now. Pick out all your new Fighter powers.” Rather than losing something special, that player just replaces all the useful powers he had with different-but-equally-useful ones.

This is the reason there’s no red or yellow in my terrible 4e photo. Since there’s no sense of one class being better than any other, there’s no reason to hold a player of a particular class to higher standards. Nor is there any sense of penalizing that player should he fail. Instead of being rare and notable characters, Paladins are just another option on the menu.

This is starting to get a bit whiny, so let’s focus on all the reasons this is a good thing. For one, not having a “base class” is a great thing! Fighters in 4e get cool attack powers and fun mechanical bonuses for a variety of different weapons. There are lots of reasons to pick Fighter over Paladin outside of “I don’t want to be lawful good” or “I didn’t roll a 17”. It also means the player who picks Fighter isn’t made to feel redundant or useless in a group that also has a Paladin, since they’re providing different functions in combat.

It also means there are no tiresome debates about whether a particular course of action will or won’t be acceptable to the party’s Paladin. The party isn’t required to throw one-fifth of its treasure into a black hole just so one guy can keep turning skeletons and laying-on-hands. The group can engage in stealth and subterfuge without the Paladin poo-pooing or sitting out.

There’s a more important benefit to this design though: World of Warcraft had redefined what the Paladin was in the fantasy genre. It still had connotations of being the incorruptable paragon of justice, but to many players he was now a combination between fighter, tank and buffbot. The value of a Paladin was measured less in how he behaves and more by how much damage he soaks up and whether he can get his allies cleansed of debuffs.

The shift in tone makes perfect sense for a more mechanically-oriented game like 4e, then. A new Paladin for a new age. Now everybody gets to play them, not just the elite few who roll really well and can stomach a bible full of caveats.

Guys like me, though, who liked the way 2e handled its stronger, rarer, more challenging classes couldn’t help but feel something had been lost. We gravitated towards Pathfinder instead.

—

Fifth Edition Paladin

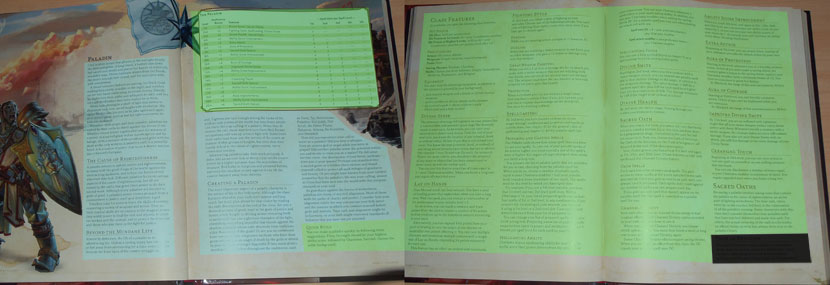

Finally, let’s look at pages 82-85 of the D&D Player’s Handbook for fifth edition, and delve into why it’s so brilliant. Superficially, the spread looks pretty similar to 4e. Like its predecessor, 5e is a game where all classes are unique and ostensibly balanced. The Paladin is therefore defined by its features and abilities rather than its roleplaying restrictions.

But good golly! Look at all that real estate! Each class in 5e gets at least a full four-page spread, and many (such as the Paladin) get considerably more when you delve into the nuts and bolts of the class. Unlike 4e, where these pages were just naked lists of powers broken up by level, the 5e character options are split into broad sub-classes called archetypes. And here’s the first stroke of brilliance: only one of these Paladin archetypes is the 2e-style paragon of justice. From the PHB:

“The Oath of Devotion binds a paladin to the loftiest ideals of justice, virtue, and order. Sometimes called cavaliers, white knights, or holy warriors, these paladins meet the ideal of the knight in shining armor, acting with honor in pursuit of justice and the greater good.”

Sound like anyone we know?

If that’s not to your liking there are two other Paladin archetypes you might try, one of which (Oath of Vengeance) is much closer to the 4e-style Paladin in terms of smiting darkness and meting out justice to evildoers. The idea here — and I’m certain this is not coincidence — is that 2e veterans look at this verbiage and think, “The Paladin is back, baby!” while 4e newcomers look at it and think, “Phew, I can still be a Paladin without having to act like a self-righteous prick!” The PHB also gently nudges players towards designing their own Oaths, giving them permission to work with their DMs to customize the character so he is challenging and satisfying to play.

Even better, a brand new 5e player doesn’t have to decide right away what kind of Paladin he wants to be. Most 5e classes don’t choose their archetype until the third experience level, so the average player will have two or three game sessions to try the character out and see how it feels. Imagine a player who starts out with lofty goals of playing the perfect lawful good character, but loses his taste for it after a couple encounters. In 2e this player is cursed to play an average Fighter for the rest of the campaign, no takesie-backsies. In 4e this player doesn’t actually exist, since nothing in any of the class descriptions rewards or restricts behavior. 5e provides the perfect, elegant solution: the Paladin takes a different Oath. A roleplaying opportunity is created as the character questions his ideals and comes to respect new ones. And the player gets to keep all his cool Paladin stuff, just pointed in a bit of a different direction.

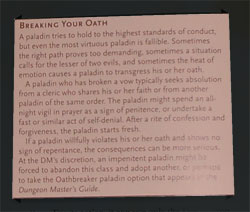

Ah, but there’s a masterstroke. You knew there was going to be a bit of red ink in the 5e book, didn’t you? Well here it is:

These are the rules for Paladins who wander from their Oath, whatever that may be. They’re clear enough that Paladin players know what is expected and what to do if they falter, but they’re vague enough that it’s easy to rationalize not bringing the hammer down. They also give two possible outcomes for a Paladin who goes too far: he either loses his class features, or gains new ones as befitting his newly-evil status. These fallen Paladins are called Oathbreakers, and the rules for them are in the Dungeon Master’s Guide. Paladins are, in fact, the only class that has rules to change archetypes. Rather than being penalized by losing powers, a creative player may consider becoming an Oathbreaker a sort of weird reward for taking his character in a new direction.

Paladins in 2e were rare and special because of their roleplaying restrictions, but that meant not every player could enjoy it. In 4e the option was available to everyone, but the class lost what had made it unique. 5e elegantly allows either style of Paladin, and many degrees in-between. And it does this without requiring house rules and without introducing the drawbacks of either of the older editions we’ve looked at. Wow!

—

What It All Means

The treatment of the Paladin is just one example of what 5e means when it says “all things to all players”. Similar examples abound in all other aspects of the game. There will always be edition purists, surely, but it’s very difficult for me to imagine an open-minded person looking at the 5e rules and not finding them better than what they’d been using.

Back when 5e was still in development, when Wizards of the Coast was using ridiculous internet polls to ask players what they liked about each edition of the game, it was very easy for me to simply declare my lifelong devotion to 2e and then drop the mic. Lots of players were likewise disappointed in the direction 4e took the game. I wasn’t disappointed, per se, but I was vocal about the game not being a good fit for my group.

The game had to work very, very hard in order to soften my coal black heart. The Paladin is one of the reasons it succeeded. A great deal of care and attention was paid to make sure fans from 1979 would feel as comfortable picking it up as fans from 2010. The class works whether you last played one in Toril or Azeroth. That was not easy, and it’s just one of a hundred things that had to go right. I applaud the effort as well as the result.

If you’ve been skeptical about trying out the new edition of D&D, consider this an endorsement. If you want to see the game in action, drop by my Twitch stream on Sunday afternoon to see it in action. Thanks for reading!

I received a friendly comment today asking why the download link for my old RPGMaker game was broken on rpgmaker.net. I don’t have a good answer for that, but I logged in to RMN and fixed it. You should be able to download it now, if you want!

Also my RMN inbox was full of ancient messages from forum members asking if I’d like to be interviewed. Apparently not, I guess!

If you want to play an unfinished RPG from 2004 that isn’t informed by anything I’ve learned about game design in the past ten years, click this here: http://rpgmaker.net/games/27/

Shantae and the Pirate’s Curse is a fantastic game, and you should play it. It’s easily one of the most enjoyable sidescrollers on the 3DS, and let’s remember this is a system that has lots of timeless NES classics available for download. Everyone on the internet is talking about how wonderful it is, and they’re right.

Everyone is also talking about how it’s the best Shantae game, too, and I don’t agree. I found Curse to be weaker than its prequel, Risky’s Revenge, in a few key ways. It’s better in some ways, too; the series is not regressing. I’m hesitant to say it’s advancing much, though. See, the original Shantae was an expansive game that had a lot of quirky gimmicks and gameplay ideas which ranged from “great” to “I have a headache”. Revenge was a much more polished experience, and a much smaller one, which didn’t have room for a lot of these ideas. What Curse does is takes the polished gameplay from Revenge and mixes all the old ideas back in, making for the most expansive and complete Shantae experience yet. And that’s the problem.

Usually when I review a game I like to get the Good Stuff out of the way first, so I can focus on the Bad Stuff, which is what I really want to talk at length about. There isn’t any Bad Stuff in Curse though, so instead I’m going to have to focus on Good Stuff With Caveats. In a nutshell, most everything I liked about Curse, even the stuff that was a marked improvement over Revenge, came with a slight tinge of disappointment.

Let’s start with Shantae’s new moveset. Instead of having a set of transformations, each of which has its own abilities and drawbacks, Shantae amasses a collection of pirate gear which changes the way she can move through the world. In gameplay terms, this was a strict improvement. It’s much more fluid and satisfying to navigate the game world without having to stop and dance every few minutes in order to change what your character can do. On top of that, all of the pirate abilities are fun to use, behave exactly like you’d expect them to, and look really cool. Because they’re always there at your fingertips, and because they’re so simple to execute, you’re motivated to play with them at every available opportunity. That’s high praise in contrast to, say, the clunky elephant form you basically only switched to when you saw a big rock.

None of these movement upgrades are breaking new ground, though. You get a slow-fall, a pogo jump, a speed booster, and so on. If there are ten traditional, off-the-shelf upgrades for a hero in a 2D sidescroller to obtain, Shantae gets five of them in Curse. Years from now we’ll look back on our favorite 2D heroes and say, “Samus had her screw attack, Alucard had his poison mist, and Shantae had her monkey dance, except for that one game where she didn’t.”

(Honestly, the monkey wasn’t groundbreaking either. “Climb up walls” is at least #9 on the off-the-shelf list I mentioned. But the requirement that Shantae actually shapeshift into an alternate form made her style of wall-climbing distinctly and uniquely hers. That’s what the pirate gear lacks.)

(I know a lot of people would argue that is exactly the point, given the events that transpire in Curse. They have a case, but that doesn’t make me feel any better about the situation.)

While each individual ability was a lot of fun to use, they didn’t really combine well. There were some screens that required a speeding triple-jump, but for the most part the game presented challenges as being isolated to one of Shantae’s items or another. This never felt like a gameplay hole in the first two games, because given the nature of Shantae’s transformations it was perfectly natural to have “monkey rooms” and “mermaid rooms” and such. The moveset has been switched up in Curse, but the level design hasn’t been switched up to accomodate, and I think that’s a missed opportunity. You’ll walk into a “hat room”, and you will use your hat to clear it, and all your other toys feel like dead weight for the duration. Remember Guacamelee!, where each new upgrade built on the previous ones? How you’d walk into a room that looked impossible, and forced you to pull off some insane wallrun-into-uppercut-into-airdash stunt? Shantae’s pirate arsenal feels like it could hit that same bright note, but never does.

The level design has its issues too. As a set of individual levels that need to be cleared to reach the end of a platformer — along the lines of Mega Man or Shovel Knight — they are terrific. (Er, mostly terrific. There’s one level at the halfway mark that consists of tight hallways packed with cheap monsters who pop out of nowhere, have invincibility frames, and take seven hits to defeat. Just plain bad.) As a freeform world you’re meant to explore and discover things in — as in Shantae and Revenge — they were unengaging. Throughout the entire game, I never once got stuck or had to stop and consider what to do or where to go next. The sensation of being able to get lost in a game world is not something I usually notice as I’m playing, but it’s something I missed after the fact.

The game is structured like this: you gain access to a stage select screen with one option on it. Upon completing that level, you get an item that opens up the next option. Each stage has this sequence of events: explore overworld area, complete a brief sidequest, complete dungeon, defeat boss. You repeat this until the stage select is full, and then you move on to the endgame.

In contrast, Revenge had a single, interconnected game world with a few standalone areas branching off of it. Its sequence of events went more like this: explore, dungeon, explore, combat challenge, explore, dungeon, explore in a brand new way, shooter section, final boss. And between each step you could add “figure out what to do next”. You had to consider much, much larger sections of the game world at once, rather than just what was in front of you. Curse is the bigger game, no question, but by slicing the content up into small chunks and settling into a discrete formula, it felt much smaller.

An example: underground labyrinths have been a staple in the Shantae series since the beginning, and Curse has more individual labyrinths than the other two games. The labyrinths are shorter, though, and there is seldom more than one direction you can take in them at a given time. Shantae and Revenge frequently had you solving Zelda-style environment puzzles, moving pieces from room to room and interpreting clues. You solved the dungeons in the first two games, and this undertaking could take a considerable investment in time. There is video evidence of me being stuck in the original Shantae‘s labyrinths for thirty or forty minutes at a stretch. I doubt I spent half that time completing any single area in Curse.

There were a lot of boss fights, and I’m sure they were all good, but I didn’t notice because I popped all my buffs and cheeseballed my way through them. Bosses were a weak spot in Revenge too though, so I won’t harp on them too much. Notable exception: the final boss was wonderfully-designed and includes a surprising but perfectly logical gameplay twist. Upon completing the game I immediately booted it back up and completed it again — simply because the fight was so great.

As for the rest of the combat, Curse mostly undoes the improvements Revenge made to the formula; we’re back to enemies that block your path and soak up hair whips like crazy. The game tries to help you out in several ways here, usually by placing monsters so they can be easily dispatched or avoided by using your pirate toys. This works fine, presuming you have the toy you need, and that you aren’t in that one terrible level I mentioned earlier. Other than that you’re left at the mercy of the shopkeeper just like you were in Revenge. The shop is a cold comfort, though, and I was disappointed with just about every item I purchased there.

For one thing, the shop only accepts hard currency. This would be fine, except Revenge had a superior system where the shop required hidden items to unlock upgrades. This was a clever system which hid the upgrades out in the game world, still allowed the player to upgrade in whatever direction they wished, and set a loose benchmark for Shantae’s power level as the game progressed. Curse maintains that player freedom but ditches the other two aspects. If you want upgrades, you can now just grind them out if you want.

As for the upgrades themselves, they aren’t great. The best ones are the ones that increase your hair whipping speed, just like in Revenge. There are new ones that increase your damage output, but these seem to only exist so you can see your on-screen damage number go up. A +1 damage increase doesn’t really matter when monsters that took three hits to kill at the beginning of the game still take three hits to kill after spending hundreds of gems.

These two issues combine in a really unfortunate way. I still felt really weak even after investing in some upgrades, which made me want more of them, which made me wonder if I was supposed to devote time to collecting gems. I admit I never spent time farming up gems to buy new stuff, but I’m sure someone out there has, and if that player was bored while doing it then Curse has committed the same sin as Castlevania II.

The biggest bummer upgrade is the most expensive one: a karate kick which is in all respects inferior to the hair whip. It does very slightly more damage, at close to half the speed, at the same range, and only on solid ground. I immediately wanted my money back. I tried to use this stupid kick in every situation I possibly could for the entire duration of the game, but it never killed anything as quickly as my hair whip and usually just resulted in trading damage with my target.

I really don’t mean to run the game down too much with all this peripheral kvetching. Understand this: the core gameplay of introducing monsters to hair whips is still really good. The controls are spot on, the monsters are varied and full of personality. Your pirate toys double as a weapons as well, so you have a lot of options. Enemies randomly drop buff items and pike balls, ensuring you have a supply of consumables even if you don’t make regular shop trips. If the enemies were a bit less tank-y this aspect of Curse would be just right. In light of all that good stuff, I’m just not sure what the RPG-style upgrades are supposed to add.

There is one bright, shining change that represents an objective, unambiguous improvement over Revenge: Shantae’s backdash move now has a considerable cooldown time, so you can’t chain backdashes together. It’s still useful as an escape technique, but backdashing is no longer faster than walking. Backdashing everywhere is by far the most obnoxious thing about speedrunning Revenge, so I’m glad this was changed. I doubt any normal player will even notice this change, but then I doubt any normal player will notice half the things I complained about in this post.

That’s as good a summary as any, I suppose: Shantae and the Pirate’s Curse is an amazing game and everyone should play it, but a bunch of things nagged at me after I finished it and reflected on what I’d played. I had a blast with it, but Risky’s Revenge is going to remain my go-to when I need a purple genie fix.

I’ve put more hours into Theatrhythm Final Fantasy: Curtain Call this week than I’m comfortable admitting. It’s a fine game, and it would be reasonably fun to blog about all of its little quirks and nitpicks. I feel like the internet is about to be flooded with peevish “why this character and not that character!?” rants in the coming weeks and months, though, so I’m going to take things in a bit of a different direction. See, playing these Celebration Games always gets me wound up to replay whatever games are being celebrated, but that’s a sticky wicket with the FF series, because Final Fantasy II.

I wonder, when it comes to Celebration Games: are developers ever embarrassed when they have to acknowledge terrible games they’ve made? Did the guys who made the Sonic ’06 level in Sonic Generations draw the short straw? Was there a furious debate over whether to put stuff from Metroid: Other M in the new Super Smash Bros.? Publically, companies always manage to put a brave face on things, but it makes you think.

Curtain Call seems a little more self-aware than many others in this regard, in that it includes nods to dozens of beloved FF spin-offs but refuses to acknowledge barrel-scraping crud like FF Tactics Advance or FF4: The After Years. Someone at Square-Enix decided to draw a line, and that line left FF Dimensions and FF7: Dirge of Cerberus out in the cold. And you know what? God bless ’em. Let’s be charitable and say these garbage games were evolutionary dead-ends in the FF ecosystem. Nothing wrong with culling the occasional vestigial limb.

But you can’t draw a line through Final Fantasy II. The title is Final Fantasy, and then a number. Just having “13” in the title of a game implies the twelve games that came before it, and in this case, one of those games was Final Fantasy goddamned II. Curtain Call includes its FF2 content only grudgingly: only two characters, three monsters, and fewer tracks than any other main series entry. It’s the hairy, oozing wart of the series.

They have tried to remake the game a couple times, but a fresh coat of paint doesn’t help when your foundation has so many giant cracks in it. Usually, they have to package the game in with its big brother in order to get people to buy it, since FF1 is a timeless game that people actually want to play. I haven’t seen the sales numbers for the PSP and iOS versions of FF2, where it was released as a stand-alone title, but I’d be willing to bet they aren’t rosy.

And yet, for all its sins, it’s an example of what I feel is the true heart of the series: FF is never shy about throwing away what came before and re-inventing itself. For decades this series has pushed at the boundaries of what RPGs were and are. FF2’s existence shows us this is not a modern development. If you played FF2 back in the ’80s, you first had to discard everything you had learned from FF1. The game knocked everything sideways. A bit too much, really; a big part of FF3’s design involved re-orienting the series back towards something recognizable. And every game thereafter featured some mixture of old and new.

There are a million negative things to say about FF2, so I’ll say something positive instead: just about every idea it introduced into the RPG lexicon is considered good design by modern standards. Maybe there is a brilliant game hiding in there, somewhere, thirty years ahead of its time. Maybe a modern remake of the game, where everything is re-built from the ground up, could be a hit.

So let’s take a break from trashing this awful game that sucks, and try instead to look at the things it has going for it. What elements does it have which, if properly nourished, could make a modern version of the game sing?

—

Point One: Firion is cool.

Years ago, during my 13 Weeks of Final Fantasy articles, I ranked Firion above the angsty likes of Tidus and Cloud. (And Squall, though replaying FF8 last year has caused me to re-evaluate my stance on Squall. But that’s another blog post.) I lumped Firion in with FF3’s Luneth and FF5’s Bartz: they were bland heroes with few defining characteristics. But that makes sense; FF2, FF3 and FF5 are all entries where the player gets to decide which characters fill each party role.

Firion has a major leg up on Luneth and Bartz, though: he looks like a badass. On the Famicom Firion was just a red-fro’d FF1 FIGHTER, but in the PS1 remake and in every version of the game since he is decked out in wicked armor and covered with colorful adornments. Since Dissidia he has been depicted as carrying around an arsenal of weapons, one of each type of the FF series has to offer.

I think the history here is interesting. In FF1 your heroes’ equipment was determined by their job, and the only notable gameplay involved in selecting equipment was “Can this cast a spell if I use it?” In FF2 any character can use any weapon, and their proficiency with it is determined by how many foes they’ve bonked with that weapon type over the course of the game. This is FF2 gameplay we’re talking about here, so it ended up being broken and stupid, but it made the player consider their weapon selections on a new axis beyond “what sword has the biggest number”. In theory characters were able to specialize, or generalize, or eschew weapons altogether and go bare-knuckled. There were interesting decisions that involved considering the properties of the weapons you just uncovered in that treasure hoard vs. what types of things your party was skilled at hitting with. Point is, the concepts of training and swapping weapons was something that defined FF2 as a whole, not Firion in particular.

But then Dissidia came around, and it had to distill the themes and concepts of each FF game into how its protagonist was portrayed. Cecil weilds Kain’s spear, Bartz equips a random selection of moves from the rest of the cast, Onion Kid uses both of FF3’s endgame jobs… and Firion became a weaponmaster. Since Dissidia has done more for Firion as a character than his original game, that’s how players now regard him.

I think a potential FF2 remake could leverage that. There’s this oldschool image of Link from the Legend of Zelda instruction manual depicting him with all of his various tools and weapons from that game strapped and pocketed on his person. That’s what modern Firion reminds me of.

—

Point Two: Players like leveling their skills naturally.

Skill advancement in RPGs tends to happen in one of two ways. Either the hero amasses some abstract resource, automatically unlocking higher stats and new abilities as he goes, or the player is handed some abstract resource and is expected to spend it unlocking the stats and abilities he wishes to use. The former style has fallen a bit out of fashion, and many modern RPGs use a blend of both. FF2 used the latter style before anyone knew how empowering it could feel, but unfortunately long before anyone knew how to do it properly.

Well, that isn’t the case anymore. As good as the FF series has always been about re-inventing itself, it’s been just as good at recognizing and stealing good ideas from other games when the opportunity arises. There’s no need to re-invent the wheel here. Fold in a skill advancement system similar to what you’d see in an Elder Scrolls game, and you have something fun and workable that would still feel very much like FF2. Want to learn how to use a sword? Use your skill points to level up swordsmanship!

As they fight in battles, characters would amass three different flavors of EXP. You spend Weapon Points (WPs) to level up your weapon skills, Spell Points (SPs) to level up your spells, and Ability Points (APs) to level your base stats. You gain WPs by hitting with weapons and SPs by casting spells. APs would increase steadily but naturally as you win battles. The higher level a stat or skill is, the more points it costs to raise it again, but there is no limit on how many points you can earn. There is therefore no bad way to spend your points — at the absolute worst, you have to fight a few battles so you can level something else. (FF10 does something similar with its sphere levels. It uses a different gating mechanic to make sure you don’t level everything all at once, but the end result is about the same.)

Two aspects of FF2’s advancement mechanics always get mentioned by people lamenting this game: leveling up HP and leveling up spells. Instead of gaining more HP as they level up, the heroes in FF2 gain it by taking damage. This sounds like a neat idea that would just kind of work itself out as you play, but in practice it fails because it stops functioning if the character is wearing a decent set of armor. Very quickly the player realizes the best way to train HP is to take off his armor and have his own party sit there beating on each other, which is an even more dull than running circles killing slimes. Not to mention thematically ridiculous. This problem is gone now, because instead of your HP going up by taking damage, you increase your HP on the menu by spending APs.

The spell system is reviled because you have to train every spell individually, there are a hundred spells, and it takes a hundred castings to level any of them up. Training one spell to the point where it’s useful takes some serious grinding; training up a dedicated mage is totally unthinkable. Instead of having a separate level for every single spell, let’s train them in categories instead. A skill for damage magic, a skill for debuff magic, a skill for healing magic, and so on. There’s a little too much going on to be able to split everything evenly into the traditional White/Black sets, but there’s also no need for nonsense like Fire 7 and Basuna 12. Without sitting down and re-working the whole list, I could see fitting everything into a White/Black/Green/Ultima system that would give the player sufficient freedom and fit FF2’s lore without blindsiding them with “Oh, you trained lightning magic? Sorry, this boss is only weak to ice.”

In addition, let’s have a class of spells that we simply acknowledge are utility spells that sit outside the system and don’t need to be leveled: Libra, Esuna, Teleport, probably the infamous Swap. These spells are useful, but stronger versions of them are not more useful, and weaker versions of them don’t make any sense. FF13 was wise to understand that spells like Libra and Quake don’t jive with its style of ATB, and spun them off into being special techs instead. There’s room for that wisdom in FF2.

Finally, we should include some sort of backdoor for players to grab a few quick levels without investing in a long grind. Vendors who sell “Axe +1” items would do the trick, as would sufficiently expensive trainers as seen in Elder Scrolls. Temporary buffs would have a place, too. Train Firion in swords for half the game, then pick up a great spear you want to use in this one dungeon? No problem, just pop that Spear + 50 potion you’ve been hoarding. Point is, the player has resources other than hours on the clock. Let’s use them.

—

Point Three: Altair makes a great home base.

The story of FF2 is about a group of kids who join the rebellion of a deposed queen. The world map is designed without borders; there are no plot flags keeping you from exploring all but a very few remote corners of it right out of the gate. (There are other things preventing you; see below.) Most of the game’s adventures involve the kids receiving orders to run reconnaisance or gather supplies for the rebellion, and every other entry on the game’s itinerary is “head back to Altair and report”.

If this sounds a bit like how modern RPGs are structured, you see where I’m going with this.

Altair could easily serve as your Ironforge or Rabanastre or Celsius airship: a place to rest and refuel between missions, a place that stocks increasingly better equipment as the game goes on, a place worth re-exploring every time the plot advances. But it has potential to be more than that. Since the kids are instrumental in the rebellion, and the rebellion is a growing thing, there should be some sense of shaping Altair into what the player wants it to be. A personal quarters filled with customizable furniture and achievement trinkets is a no-brainer.

Queen Hilda is the one who gives the plot missions, as it should be. But everyone else in the rebellion is fighting too, and the more you help them the faster and stronger Altair should develop. One of FF2’s earliest missions has you securing a supply of mithril for the town blacksmith. Keep that in as a sort of “introduction to sidequests” mission, then expand on it through the rest of the game. I’m picturing something like the Clan Centurio job board from FF12, except with the singular goal of aiding the military exploits of the rebellion.

We know players love gathering materials, securing resources and crafting items. (See also: FF8, FF10, FF12, FF13.) These ideas fit in well with FF2’s established game systems and with the theme of a growing military. Instead of finding a Blood Sword, you would find a rare Bloodstone Ore which you turn into your blacksmith to augment whatever weapon your hero was skilled with. Instead of spell tomes being rare monster drops, have an NPC in Altair sell them to you in exchange for magical components.

The goal here is twofold. First, we want Altair to be more engaging to the player than simply “that place you have to keep walking back to over and over again”. And second, we want to retain that sense of slowly improving your party’s abilities without it just being a naked grind. How better to hide said grind than behind hours of sidequests? Especially if those sidequests have the satisfying side-effect of seeing your base expand and grow?

—

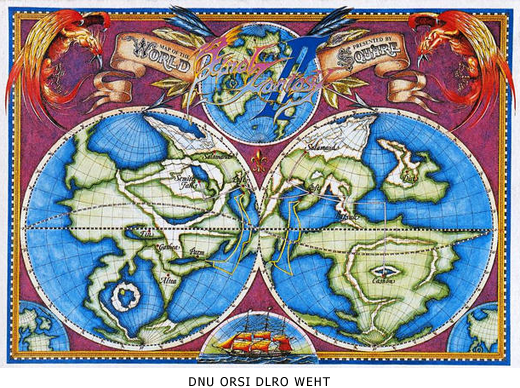

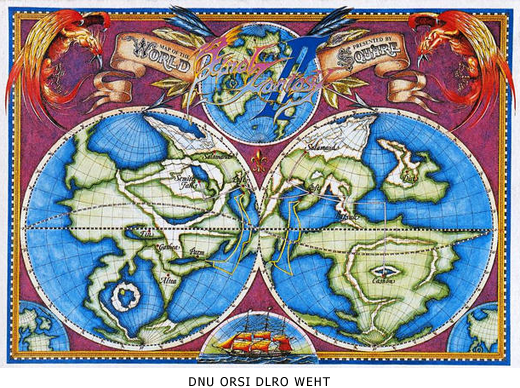

Point Four: The world map is explorable in every direction, and there are lots of directions.

FF2’s world map is the only retro JRPG I can think of that isn’t surrounded by ocean on all side. It’s also the only one I can think of where the player is never boxed in by inconveniently-placed rivers or mountains. Nowadays we enjoy this freedom in most every RPG we play, but in FF2 that freedom is only an illusion. You can walk all the way from Altair to Mysidia, but in practice the monster hordes make this impossible. But then, FF2’s revolutionary “save anywhere” system downgrades the trip from impossible to merely excruciating, which transforms the journey from an adventure into a boring slog involving lots of saving and resetting.

Turning FF2 into a boring slog is, in many ways, the most efficient way to play the game. Which is too bad. But it doesn’t have to be that way! Just turn the dials back on the monsters so your party doesn’t go from wimpy bugs and blobs to bone-crunching stun-locking nightmares in a single step, and you’re halfway there. We still want the player to be able to get in over his head, though; that’s part of the fun of a huge RPG world. Running away from fights was a hassle in FF2 because it’s an archaic turn-based RPG. If you tried to Run, and failed, you usually just died because that’s how these games used to roll. Fortunately FF4 provides our solution: a Run command not tied to a menu or combat round. Hold your shoulder button (or touchscreen equivalent) to run away, even while you or the monsters are entering other commands. Now careful explorers can identify their limits without risking a party wipe, and those crazy enough to strike out early for Mysidia only need a little luck rather than a dozen resets.

Next we need to inject some juice into the world. There was no reason to explore every corner of FF2’s map originally, but now that we have a robust crafting system, a delivery mechanism for sidequests and a home base to expand there is no reason not to. And since we aren’t limited to 8-bit hardware anymore, we can make the terrain more exciting than huge expanses of field or forest.

There’s one more really great bit of FF2 lore we can capitalize on: the chocobo forest. This was originally a secret area, something for players to discover. Nowadays everyone knows about it, but we can use its “open secret” status to breathe some life into the game. Reach into FF9, pick out all the chocobo elements from that game, and plunk them in. Complete a sidequest befriending the world’s last remaining chocobo, give the player the limited (but not exhaustable) ability to summon that chocobo anywhere on the world map, and include a treasure hunting aspect that the player can get lost in for hours.

The treasure hunting thing world work especially well, I think. Even using the same mechanics as FF9, veterans from that game would have to approach it in a different way. FF9’s world was several smallish continents surrounded by ocean; FF2’s world is one gigantic continent enclosing a single ocean. There’s no need for FF2’s chocobo to have to run on water, so players would really ride around on their bird looking for hotspots rather than flying around in their airship. Plus, since we have a need for a diverse range of stat-up items, spell tomes and crafting materials it will be easier to have lots of meaningful mid-range treasures. (Contrast with FF9, where you’d open a box and get 80 Hi-Potions.)

Now that we have a huge world and tons of stuff to find, we can expand upon those special, un-level-able utility spells I mentioned earlier. Have one spell that dings when you close in on hidden treasure. Have another that helps find the location of particular monsters. Have a third that sets and activates warp points, to help mitigate all the traveling we’re doing.

—

Point Five: The party system has lots of space in it.

FF2 is the first JRPG I know of with a cast of rotating characters. Three of your party slots are static, filled with the games main characters, but the fourth slot is a revolving door of heroes. A new face every few adventures, in fact. Many of these characters are prototypes for folks we’d meet later in the series: Leila the proto-Faris, Leon the proto-Kain, Gordon the proto-Edward. It’s a fun system, and it helped the player to feel a little more involved in the plot than other games of its day.

Unfortunately, that fourth character was governed by the same rules and mechanics as the rest of the group, which meant they hadn’t spent hours casting Cure over and over or letting Firion punch them repeatedly. Which meant they were weak and useless. Which meant players tended to regard FF2 as having a three-man party up until the final dungeon. With the changes we’ve already made, the party system could use a bit of an overhaul.

First, let’s mostly dump the “anyone can do anything” motif from the original. We wan’t to capitalize on Firion’s image as a weaponmaster, but we can’t do that in a whole game full of weaponmasters. Instead, let’s restrict each of the three main heroes in one aspect of advancement. Firion has middling stats and gains few SPs, but earns WPs very quickly. Maria likewise has middling stats and few WPs, but has the most SPs. Guy has naturally high stats and the most APs, but earns fewer WPs or SPs than the others.

If certain types of equipment lowered your magic stats enough, that would help both Firion and Maria to find their niche very quickly. Maria could equip anything, but she levels weapons slowly, and anyway putting her in plate would reduce her magic effectiveness. On the flip side Firion can cast anything, but because you want him decked out in heavy gear his spells will never be as effective as Maria’s. There’s a clear path for the characters to develop, but if you’re in an emergency and you really need Firion to Cure or for Maria to equip a Frost Brand, you can.

I see Guy as filling the black belt role. FF2 already has a weapon skill set aside for unarmed combat. Let’s keep the tradition where unarmed fighters take a penalty from heavy equipment, and make Unarmed the only combat skill that levels with APs instead of WPs. This makes him into the black belt from FF1: raw, unfocused damage output. Plus, it’s a knowing nod to FF2 veterans who already play the whole game unarmed, because the weapons system is so totally borked. Guy’s magic would still be worth leveling, too, since his stats are higher than Firion’s and he isn’t weighed down with heavy gear.

The goal here is to leave in the idea that anyone can do everything, with the asterisk that characters still have specialties you should focus on. Something similar to FF10, where most players are satisfied following the pre-determined path, but really determined ones can diversify and max everyone’s everything.

The guest characters don’t really need much consideration, since they’re mostly window dressing. Let’s use the main heroes as templates, make them follow the same rules, but give them pre-set levels in certain skills. (Minwu is Maria with most of the white magic already mastered, Josef is Guy with really low magic stats, Ricard is Firion with maxed-out Spears.)

(Gordon maybe has middling stats and earns all EXP slowly, to solidify his station as Brave Guy Who Means Well But Doesn’t Belong On The Battlefield.)

That just leaves Leon, the character who joins for the endgame. By this time in the game the player should have a good handle on all the stats and skills, plus a reserve of booster items. In that case, Leon could join with slightly-below-average everything, but gain all EXP at the increased rate. This makes him the “best” character by far, but most players won’t notice because the endgame is so close.

—

Point Six: There are lots of plot elements to work with.

FF2’s plot sucks, but only in the sense that every RPG plot from the ’80s sucks. The Famicom just wasn’t capable of pushing the amount of text needed to flesh out a full, well-realized story. That’s why so many of our favorite 8-bit RPGs are just strings of fetch quests with no cutscenes. FF2 tried to involve the tactics and machinations of an advancing war front, as well as rich mythologies and histories to explore, but it was running on hardware designed to run Super Mario Bros., so it fell quite short of the task.

This is easier to fix than the rest of the problems with the game. We don’t need to pack every scene full of CGI-laden exposition, but there is lots of space for the plot and setting to expand into. Who exactly is Paul, the mysterious thief who aids the rebellion? Why did Leon suddenly switch sides? How were the dragoons of Deist defeated by the Empire? What is the point of having a coliseum built in the middle of an otherwise featureless desert? Why are the chocobos so near extinction, and is there a way to help rebuild their numbers? How can we expand on the Mysidian lore surrounding magical masks and forbidden magic?

One thing we can probably just do away with is the asinine keyword system FF2 employed. Originally this was intended to give the player some sense of conversing with NPCs in the game world, but it’s held back by the same limitations as every other system in FF2. This is an example of one of those vestigial limbs; a point in the series development that didn’t lead to anything substantial. There are ways to make the player feel like they are seeking and discovering knowledge, but a clunky keyword system isn’t how it’s done. At the end of the day we still want FF2 to hold close to its JRPG roots. Building on the old keywords would lead to dialogue trees, or something like, and that puts us further from our mark.

—

Point Seven: It is a Final Fantasy game, for goodness’ sake!

As terrible as it is, and as much as everyone hates it, Final Fantasy II and its various remakes is still part of the most famous RPG series on the planet. As long as the series continues to engage in thoughtful callbacks to its roots, and as long as Square-Enix continues to gut our wallets with future installments of Dissidia and Theatrhytm, FF2 will remain a recognizable title in the gaming landscape. If it were some obscure RPG nobody cared about — Arcana and Legend of the Ghost Lion spring immediately to mind — it wouldn’t be worth fixing.

But it’s not. It’s Final Fantasy. Its legacy is already secure. More than that, though, is the whole point of this entire article: in the decades since FF2’s release, RPG developers and players alike came back around to its ideas. Modern players would enjoy a version of this game made in 2014, with 2014 sensibilities. FF veterans disillusioned with the series’ HD output would enjoy an actually-playable romp through one of the genre’s most oldschool offerings.

And old fanboy turds like me could finally stop losing sleep about about how much this stupid game sucks. At long last.

Thanks for reading!

If you like board games, there are two new releases on Steam you might want to check out. They are Tabletop Simulator and Chess 2.

—

Tabletop Simulator

I don’t think any video game exists with a more apt title. For your $15 you get a table and a big chest full of physics objects to move around. These physics objects can be manipulated by any player at the table, and can take any shape or size in whatever quantity and configuration you need. If you need, say, 52 flat, rectangular objects with suits and numbers on them, you’re good to go. Or 64 chips with white and black sides. Or isometric dice and a beholder.

The game — to be more accurate, the sandbox — makes no attempt to inflict or enforce any rules. It just supplies the pieces. It has a few old classics built in, Chess and Poker and Parcheesi and the like, which you can play as-is or modify however you want. Play Chess with all bishops or Poker with all aces, or just sit there throwing Parcheesi pawns at each other. When you get tired of that, you can use the in-game editor to design your own games either using the supplied chits and dice or crafting your own.

Or, if you’re like us, you’ll prefer to browse the Steam Workshop for mods other people have created. Most every board game you have in your cabinet right now has already been ported over, from Monopoly to Arkham Horror to Nicolas Cage Guess Who. (I hope this is the only board game night I ever have that involves the question, “Is your Nicolas Cage on fire?”)

The real magic of Tabletop Simulator, of course, is the ability to play all of these games with people who aren’t able to sit down at your real-life table with you. For some reason the board game industry has not been very diligent in offering virtual versions of their products, and so Tabletop Simulator has stepped in to fill the gap. The multiplayer aspect of the game is surprisingly seamless: one player creates a lobby, then everyone else joins. Your lobby can be password-protected to ensure random people don’t drop in. Or you scroll down the list of publically-available lobbies to see if any strangers are playing your game of choice. Everyone can play even if only one person has the game, which eliminates all that annoying “wait a minute, so-and-so needs to install the mod” downtime. There is an in-game text chat so players can communicate and/or heckle one another.

Since Tabletop Simulator doesn’t actually know what game you’re playing, it can’t enforce any of the game’s rules. In theory, this means players can move each other’s pieces or otherwise attempt to ruin the game by cheating or trolling. Points against, sure, but these same behaviors are part and parcel with the physical board game experience, and you deal with them the same way: by kicking the player out and continuing to play without them. There is also strength in such lawlessness: rules are as easy to invent as they are to break, opening the door for any number of house rules your little heart desires.

The sandbox’s movement and camera controls are a little cumbersome, and the physics can act in odd ways sometimes, but this is a small price to pay to be able to play board games with people who, until now, I’ve only been able to talk about board games with. The tagline we kept repeating in my Twitch stream was, “For $15 you get every board game ever.” That’s not strictly true — more physically demanding board games like Jenga or Mouse Trap are impossible in the current sandbox — but it’s true enough to keep us amused into the foreseeable future.

—

Chess 2

I thought it was an eyebrow-raising decision for David Sirlin to initially release his sequel to Chess as an OUYA exclusive, because who even has one of those? But now that the game is available on Steam (and I think iOS?) I’m actually dying to try it out. I love Chess, but I’m a bottom-feeding novice, and I have absolutely no desire to memorize endless variations of game openers or to play against opponents who have done that. Chess 2‘s promise of asymmetrical gameplay and alternate win conditions got me really excited.

But not excited enough to spend $25 on it. That price is outrageously high for a virtual copy of a board game.

I’m sure Sirlin would say that $25 (really only $21, thanks to the launch sale) is a drop in the bucket compared to how much competitive fun I will get out of the game, and he may very well be right, but we don’t live in a world where video games are priced in terms of dollars-per-fun-unit. We live in a world where I could take that $25 and buy Shovel Knight or Freedom Planet or Crypt of the Necrodancer plus a footlong sub sandwich.

Or I could just wait for someone to make a Chess 2 mod for Tabletop Simulator. Oh look, someone already has.

Hi! I’ve completed a few more fusion bead projects you might could look at, if you want.

Ibuki from Street Fighter as a robot master. I sent this one to a viewer who plays a really mean Ibuki during our Scrubbin’ Bubbles streams. I can’t take credit for the Mega-Man-ization; it’s just something I found on the internet somewhere. There’s a whole batch of these, so I’ll have to do up T. Hawk one day.

Peanut wanted a duck, and what Peanut wants, Peanut gets. He lives next to our TV now.

Maria from Castlevania: Rondo of Blood and grown-up Maria from Castlevania: Symphony of the Night. I didn’t realize until I beaded this out how little of a face Maria had in Symphony.

Blue Mage Butts and Kitty Krile from Final Fanatsy V. I wanted to finish up the rest of the team, but I ran out of black beads. Once I get my delivery I’ll probably have to do up a six-armed Gilgamesh for them to fight.

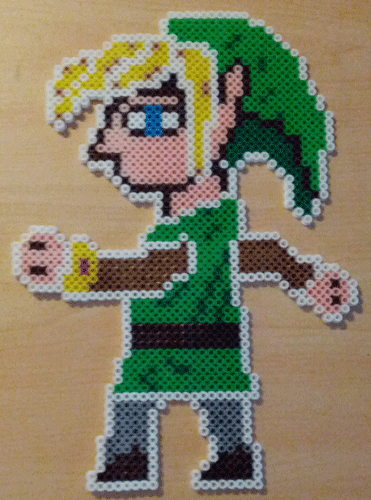

Having no black beads severely limits the patterns I could make. Fortunately A Link Between Worlds offered a unique opportunity to bead a character with a white border! This is the first perler I’ve made that isn’t a 1:1 pixel re-creation, and I was quite worried about how it would turn out. I started with a grainy screenshot from A Link Between Worlds in Photoshop, reduced the color depth by as much as I could, and then hand-selected the color palette I’d use. I’ve got a few more patterns made using this same technique, I’ll have to make sure I translate a few more of them into beads.

Folks in my Twitch chat always have lots of questions about the perler-ing process. I’ll have to write up a comprehensive how-to guide next time I tackle a large project. Which should be… uh… as soon as my delivery gets here, actually! Thanks for reading.

You attend the annual Halloween event at your local theme park. You get a brochure that lists all the haunted houses, and each one has a little story. The story for Outlast reads: “Paging Dr. Trager! The evil Murkoff Corporation has recently acquired the Mount Massive Insane Asylum, and the inmates are restless! Will you unravel the mysteries of Father Martin’s dark cult? Or will you join the mutilated patients who inhabit these haunted halls?” Of course, there’s not really a mystery. You go in the front door, turn lots of tight corners, and an inmate with his guts hanging out jumps off a bed and lunges at you. At the end, you put your 3D glasses back in the big bin and muscle passed a group of teenage girls giggling about how totally scary the guy with the chains was.

There is a burgeoning industry within the greater community of streamers and Let’s Players catering specifically to the “haunted house” genre. A murderous zombie suddenly rockets onto the screen, accompanied by a shrill violin sting and a spray of blood, and the player screams his head off (much to the delight of the viewership). You don’t have to poke around YouTube very long to see guys who have built their entire channel on this type of reaction. Feeding into this industry are a new generation of horror games, of which Outlast is one. Since the thrill of the game is in the scares, and those work whether you’re playing the game or just watching it, the developers can get away with having as little gameplay as they care to design. That sounds really harsh, but that’s how I came away from Outlast: it’s not a game that’s meant to be played and enjoyed, it’s a a game that’s meant to be gawked at, consumed quickly, then thrown away by an audience eager to move on to the next jump scare.

I say all this as a fan of stupid, shallow horror movies. I remained a fan of the Saw films even after they discarded the psychological element of their horror and ramped up the gore instead. I will preach the merits of the ridiculous death scenes in Final Destination to anyone who will listen. I have spent long, sleepless nights cruising Netflix watching B-list, no-talent, gore-for-the-sake-of-gore movies. I recently watched a movie where a man is snapped by a giant apple slicer and stands there watching his body fall apart into one-inch cubes. Once it was over, I immediately watched the sequel.

But is any of it scary? Of course not. It’s just a pile of dumb gibbets. You can tell, after you’ve waded through the gibbet-piles long enough, which movies are serving it to you with a wink and a hefty helping of self-awareness, and which ones really think they’re aspiring to successful horror. The former group is fun, if forgettable. The second is just sad. And that’s the group Outlast is in.

Let’s get the gameplay out of the way first. Outlast has two game mechanics. It does not have three game mechanics. They are: 1) Run and Hide, and 2) Find Batteries.

Run and Hide means the protagonist cannot fight, evade, disable or otherwise incapacitate his enemies. When confronted with a monster he must run away and hide from it until it loses interest in him. Every single enemy encounter in the game involves dropping the player into a confusing maze of hallways, identifying the predetermined hiding places ahead of time, triggering the bad guy, running back to the hiding place, and waiting for the bad guy to go away. Once you know which hallways to turn down, and which hiding spots to use, you go to the next area and do it again.

Find Batteries is what you do during the downtime between encounters. You have a flashlight, which you need to see in many of the game’s areas. This flashlight chews through batteries at breakneck speed. This introduces an element of resource management into the game, similar to how Resident Evil had a finite amount of ammo and ink ribbons. We know, of course, that the game won’t really let us run out of batteries, because then it would be unplayable. Every room you visit contains a plot flag, a document, a battery, or some combination of those things. So the degree to which this mechanic works is questionable.

I think it’s fair to say that the gameplay is pretty thin. This bothers me a lot as a “Gameplay is King” kind of guy. If your game only has two game mechanics, and neither is interesting or well-developed, you are going to have a very difficult time keeping me engaged. At that point you are trying to sell your game on the strength of its writing, or its setting, or its aesthetics. And Outlast isn’t strong enough, not even by a longshot. If the interactive element is weak by design, your story has to be a masterpiece. Your characters require incredible depth and vision. Your attention to detail needs to be microscopic. To put a really fine point on it, Journey is a paragon of graphics, music, world design and emotional engagement — and I didn’t like it because I got bored with all the walking and flying around.

The task is doubly difficult for horror games, because the horror genre — the ones that are really trying to be scary and not just buckets-o-gore — is as much about what you don’t show as what you do. The best horror movie directors know when to show something horrifying, and when to leave it to the audience’s imagination. They know how long to hold a tense moment. They know to how much pressure to release so the next scare is all the more powerful. The experience has to be crafted and babysat in ways the action and adventure genres don’t. In other words, the very nature of interactivity in video games works against horror stories. In a video game, you can’t not show the monster.

An example: a thrilling chase scene in a horror movie usually only lasts a moment or two, because chases are by nature high-adrenaline moments leading to some kind of resolution. In a video game, one possible resolution is “the player doesn’t get caught, but also doesn’t find the next plot flag”. I got Outlast into this state repeatedly, in which case the chases would drag out for as long as I wanted them to. (Usually this happened accidentally, but sometimes I did it intentionally just to show everyone how silly it was.) Twice I was running away from the chain-rattling murderer only to turn down a hallway and hide in a spot the designers didn’t intend. Said murderer stood there, a few feet away from me, glancing around like a guy looking for the bathroom in a restaurant. Sometimes he would get bored and wander away, resetting the chase. Dramatic music continued to play, loud heartbeats continued to throb, but the tension was totally deflated. What fun is a chase scene the second time around?

Another: I have really terrible spatial awareness in games, and died a lot as I got lost in the maze-like passageways. The penalty for death in Outlast is very slight; you just respawn at the beginning of the area. As a result, I stopped being afraid of the bad guys. I stopped caring if they caught me, because I had no investment whatsoever in staying alive. I had a lot more success with the game when I stopped treating it like a desperate struggle to survive and started treating it like a video game with a quick-load function. “I’ll run into that room and let the guy beat me to death while I look around for the exits. Then, when I respawn, I’ll know exactly which direction to run.”

I realize I’m contradicting myself. On one hand I balk at Outlast for having barely any gameplay, and on the other hand I deride it because the gameplay it did have ruined my experience as a horror fan. It’s a hard problem to solve. Most horror games — most video games in general, really — solve it by giving the player something engaging to do once they realize the writing is substandard. Nobody cares about the motivations of the bug monsters in Halo, but it doesn’t matter because they’re fun to shoot. Everyone rolls their eyes when Grand Theft Auto tries to take itself seriously as a crime drama, but then they’re happy again in the next scene when they’re driving an ambulance through a shopping mall. Outlast doesn’t do anything to fill in the “This is stupid, but _________!”

As horror, Outlast is strictly lukewarm. The writers had a bag of moldy tropes at the ready, and used each one liberally. Body parts in the toilets. Messages scrawled on the walls in blood. Anonymous torsos laying around. Phones left off the hook. Rust. Debris. Mutilation. A thunderstorm. Scattered diary pages written by dead people. And far, far more jump scares than is reasonable. They come at measured intervals you can set a clock to. I don’t know how many times I commented, “Aren’t we about due for our next jump scare? Oh, there it is.”

What’s lacking is any semblance of emotional connection. To really freak me out, you have to get in my head. You need something psychological, something introspective. “This is scary because it’s dangerous!” isn’t good enough. Heck, Tomb Raider and The Legend of Zelda do that. Being at risk of death, in a game, is not in and of itself a reason for dread. Being shocked or startled isn’t the same thing as being frightened. Mortal Kombat wasn’t billed as a horror game, but that’s the bar Outlast aspires to.